Button collectors, like all collectors, are varied in their focus, but most share an interest in the where, when and what their buttons were made of.

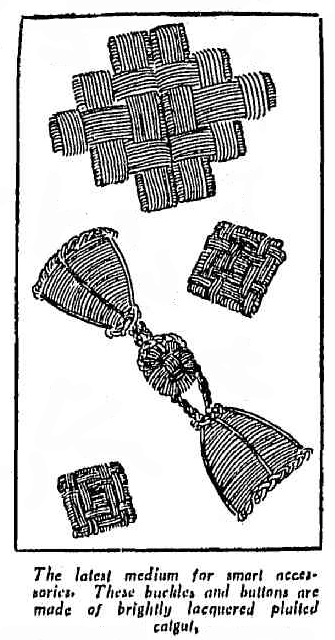

MATERIALS

Bamboo

Bamboo are a diverse group of evergreen, perennial grasses. They have been used to make buttons cut into slices, or longer portions to make toggle type buttons.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 4th August 1934 page 12.

Image from January 1958 magazine.

Blood

See Hemacite under Plastics.

Bone

Bone has been used to make buttons since the 17th century, and probably earlier. It was in great use in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but was gradually replaced by other materials. The buttons ranged from very plain underwear and trouser buttons to ornately carved, inlaid and painted. The bones used were mostly from cattle, but also from pigs, camels, whales, antlers from deer, and even feral dogs! The bones were cleaned, boiled to soften, then sawn open, scraped and pressed flat. Button blanks were then sawn from the flattened material by hand or lathe. They were then covered with material or drilled: centrally for a pin-shank, or with several holes for a sew-through type button. Disks of bone were veneered with other materials.

See also Turtle shell entry.

Catgut

Cat gut, despite the name, is cord made from fibres from the intestines of animals such as sheep, goats, cattle and others.

Warwick Daily News (Qld), 30th June 1934 page 9.

Excerpt from a longer article in the Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 8th December 1900 page 41.

Coral

Coral has been harvested for use in jewellery and carving since the 15th century, then button and buckle making in the 19 and 20th centuries. The colour, varying from white to red, is due to traces of manganese in the calcareous skeletons of the coral polyps. The rare black coral was also used . Buttons could be made of it, or the material used to embellish buttons of other material.

Liverpool Herald (NSW), 27th July 1901 page 9.

https://www.pinterest.com.au/buttonloversgroup/carved-coral-buttons/

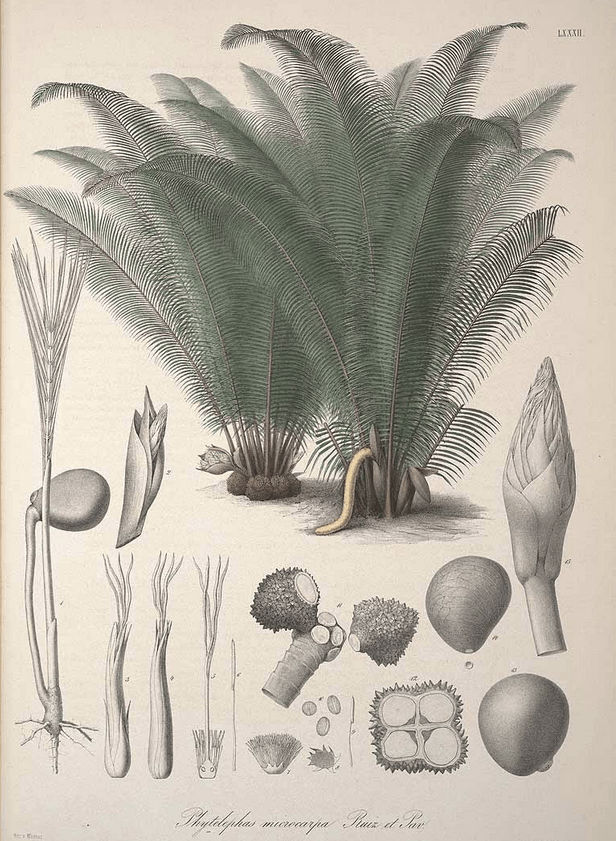

Corozo

Also known as Tagua nut, ivory nut or vegetable ivory.

If you have read my page on tailors’ buttons you’ll know that they were commonly made of “vegetable ivory”.

This very hard, white substance is in the main sourced from the seeds of a variety of South American palm trees, Phylelphous macrocarpa, although some other varieties from other parts of the world are used. These particularly grow around the Magdelena River in Colombia. The first export statistics available from Colombia date from 1840, and from Ecuador from 1865. In Columbia the export industry declined in the 1920s and had finished by 1935. A remnant industry for button production and souvenirs remained in Eucador. Since 1990 an initiative to promote sustainable rainforest industries has increased production.

Historically, it was claimed that Tagua nut was made of hardened albumen but this was in error. According to an article in the Food & Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations document repository the ” endosperm of tagua, the vegetable ivory, is composed of large, thick-walled cells, whose main components are two long-chain polysaccharides – mannan A (45-48%) and mannan B (24-25%), cellulose (6-7.5%)”.

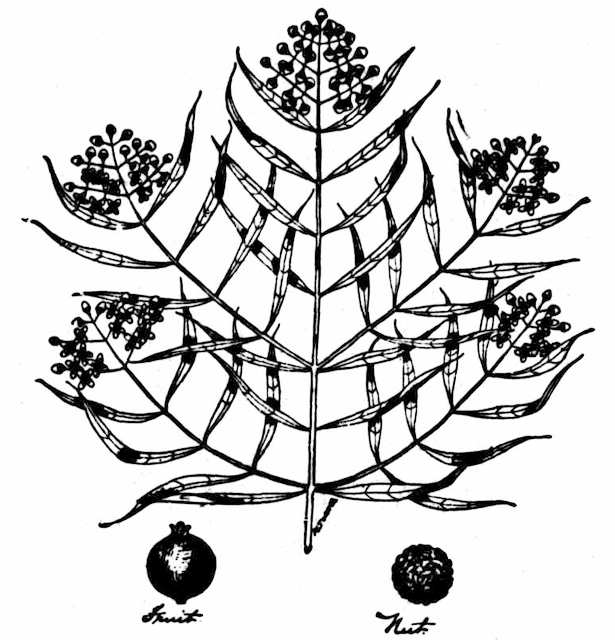

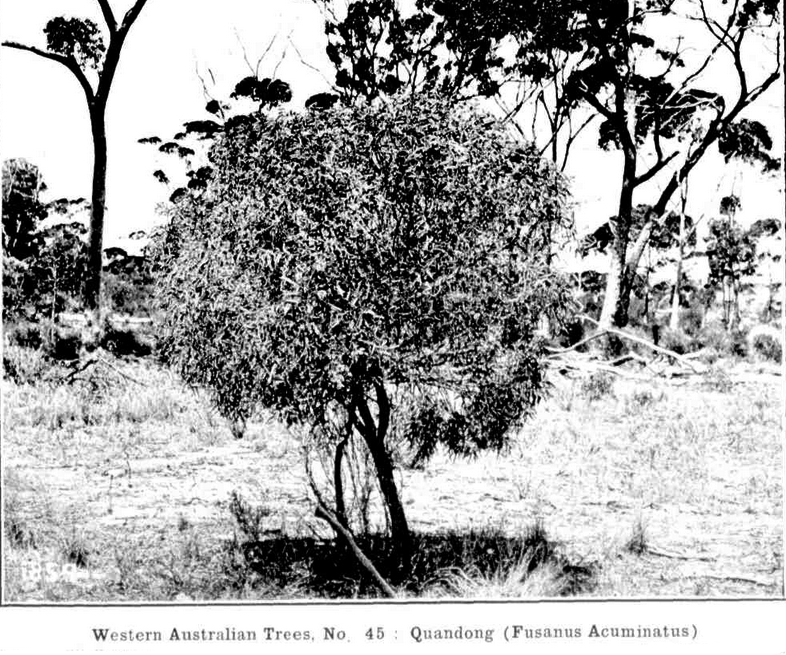

The palm tree was first described by Europeans in 1798. It was also noted at that time that the locals carved objects such as toys, walking stick knobs and reels from the kernels. The trunk is short, rarely higher than 6 foot, from which grow a tuft of large, feathery leaves. The fruit occur in clusters around the base of the leaves on short stalks. The palms have male and female individuals, with only the females producing the nuts. The fruit is 25-30 inches in circumference and has a woody covering with 3 to 5 lobes, within each lobe occur 6 to 9 large, hard, smooth, oval to spherical seeds of a grayish-brown colour. These are the “ivory nuts”. The fruit take about 2 years to ripen, and then fall to the forest floor.

Florae Columbiae, vol. 1: t. 82 (1869): Phytelephas macrocarpa

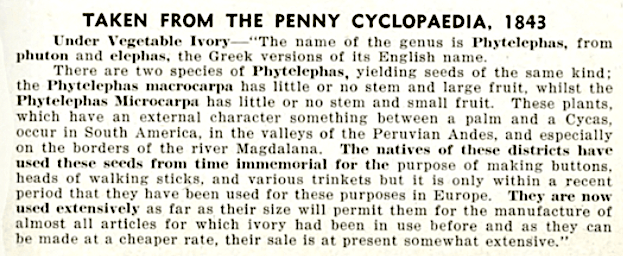

The “Penny Cylopedia” printed in England in 1843 stated that vegetable ivory was already a significant material used by button manufacturers.

On 12th August, 1843 the Indiana State Sentinel reported that ” the English are manufacturing a variety of fancy articles out of the nut”. Do not believe the oft quoted “fact” that tagua nut buttons were invented by the Austrians in 1859. Their own local industry, perhaps. The Historical Dictionary of Ecuador by George M. Lauderbaugh states that along with cacao and sugar, in 1835 Ecuador’s other main exports were “Panama hats, balsa and tagua (ivory) nuts used in the production of buttons” which means the trade started earlier. The Cultural History of Plants by Sir Ghillean Prance,and Mark Nesbitt states that “Sir William Hooker may have first introduced vegetable ivory to England in 1826” although of course that does not mean it was used in manufacturing that early.

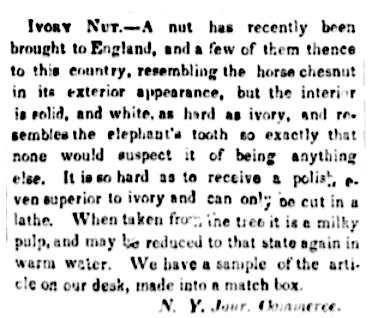

Sunbury American and Shamokin journal. [volume], October 21, 1843. ‘Ivory nut’ was known in North America and England by this date, earlier than claimed for the Austrian industry.

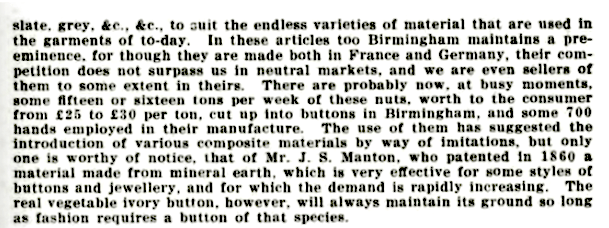

In Around 1847 thirty tons were shipped to the USA. Birmingham button makers started using the nuts around 1858, as the cost was much less than for real ivory. Perhaps 8-10 thousand gross were being made per month in that city. Their value increased from $20 to $75-80 per ton over the decade from 1866.

From “the Resources, Products, and Industrial History of Birmingham and the Midland Hardware District, edited by S. Timmins, 1866; it suggests the industry became mainstream some time between 1856-1866.

In 1913 it was reported that the principle markets for Tagua nuts were London, Hamburg, Le Havre and New York. From there they were distributed to factories in Southern Germany, Italy, London, and Birmingham. In 1920 approximately 20% of buttons used in the USA were of vegetable ivory.

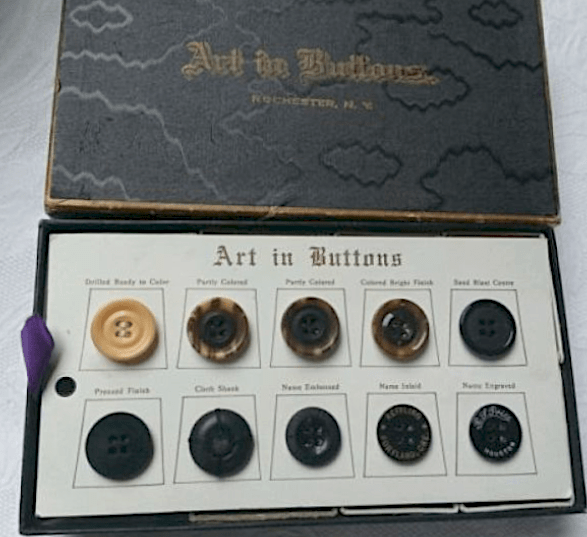

The nuts were dried from 3-6 weeks then the hard shells removed in revolving drums. They were then cut into slabs, soaked to prevent cracking, then turned on lathes into button blanks. They were drilled, shaped and polished. Although the whiteness of the nut yellows in air, it may be dyed and polished. For example, sulphuric acid coloured the nut magenta. Other chemicals, such as potassium iodate and mercury chloride could be used.

Art in Buttons (Rochester NY 1904-1990) sample box.

The buttons continued to be favoured for suits and coats until World War 2 when they became unavailable, then plastic started to take over. It remains in use, but only in small quantities, which is a shame as it is a sustainable option.

Daily Mercury (Queensland) 9th August 1940 page 10.

Fish

See also ‘Leather’ below.

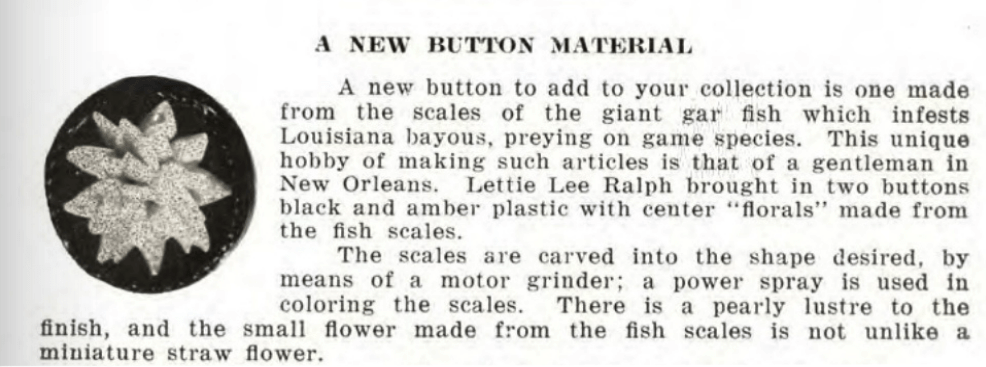

NBS Bulletin, November 1948 page 369.

Barramundi Leather Button

Gemstone

Buttons have been made of both semi-precious and precious gemstones. The precious, diamond and similar, were worn by the rich and powerful mainly from the 14th to the 18th centuries. Apart from museum examples, few survive. Due to their value, the gems were re-used for new buttons or jewellery. Cameo buttons were originally carved from gemstones.

Most buttons described as “jeweled”, are not, if fact, decorated with real jewels. From the 18th century glass (paste/strass) was cut like gems in imitation of diamonds. Coloured glass has also been used this way.

Quartz varieties such as agate, cornelian and onyx. Shirt and vest buttons were advertised for sale in Sydney from 1821, and still being used by high fashion houses in 1950. Marcasite (iron pyrite), were used buttons in the mid 19th century. Rarely materials such as jade, lava and granite have been used to make buttons.

Gutta Percha

See under Rubber.

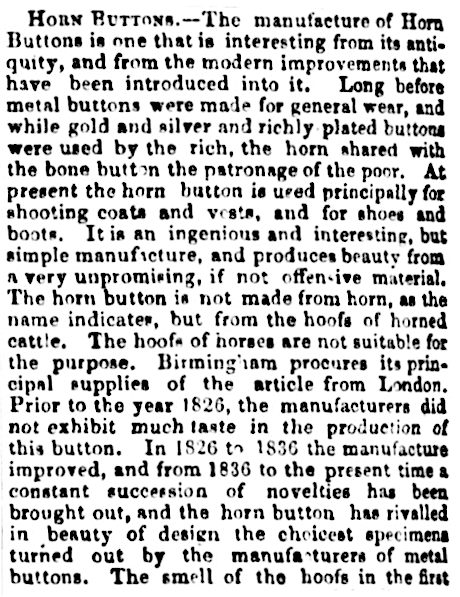

Horn Buttons

Both horn and hooves consist of keratin, which can be moulded when heated. There were horn button manufacturers in Birmingham in the 1770s. Horn buttons were imported into the Australian colonies from early in the 19th century, if not earlier. They remained a staple product into the 20th century.

The solid tips could be simply cut into rounds. Whilst those of cattle were most commonly used, that of other animals were also used. Quoting Charles Dickens writing for the Penny Magazine in 1840;

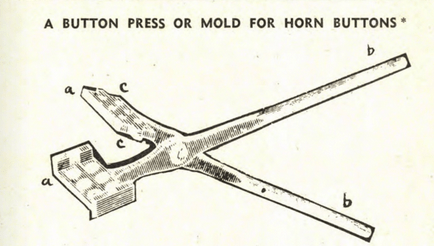

“Cow hoof were boiled in water till soft and then cut in parallel strips by a cutting knife which acts as a lever by having a hinge at one end. These slips, which are of the width of the diameter of the button, are then cross cut into small squares and the angles cut off. The pieces are dyed black by being immersed in a caldron containing logwood and copperas and then dried. A mould is formed something like a pair of pinchers, each half having 6 or 8 small steel dies fastened to it, each die containing the intended impression of the intended button embossed upon it.”

National Button Bulletin, March 1947 page 103.

“When shut close, the opposite dies exactly correspond and represent the entire shape of the button. The mould is heated somewhat above the temperature of boiling water, a piece of horn is placed upon each impression in it and the mould is then closed, and then confined within a powerful press or vise. The united action of the heat and of the pressure forces the pieces of horn to take the exact impression of the two halves of the dies and they come out in the form of buttons, plain or embossed, as the case may be, but with an outer edge a little ragged, this roughness is removed by filing, the button held in a lathe.”

“If the horn button thus made is to have no shank, four or five holes are drilled thu it by an ingeniously constructed lathe, but if shanks are required, these must be firmly united to the horn. The shanks are made in a curious manner. brass or iron is wrapped spirally round a steel bar by the rotation of the bar in a lathe. The coil is then slipped off the bar, forced into a somewhat oval form and then cut thru its whole length with two disengaged ends. More recently a little machine has been invented, which by the simple turning of the winch, supplies itself with wire from a reel and delivers it cut and bent the proper figure of the shank; each turn of the winch form a shank. Shanks such as these are inserted in the horn by children who, previous to the pressing into the mould, drill a hole into each button piece and insert the shank. The mould has a cavity for receiving the shank and the pressure closes the horn about it so effectually, that it will not come out. Sometimes horn buttons are made plain, and then have a pleasing device made upon them by placing on their surface a thin plate with a pattern cut in it. by rubbing over the plate with emery powder, the horn will become scratched or deadened thru the holes in the plate, but left polished at other parts.”

The prepared horn buttons could be dyed to imitate more expensive materials such as turtle shell. They could be inlaid with decorative materials such as pearlshell whilst still warm and malleable. Even scraps of horn and hood could be used by powdering then heating and compressing. The industry provided a source of extra income for meat processors.

Real horn feels cooler than plastic. The surface will show slight imperfections/variations, although this is harder to see if the button has been dyed a dark shade. Even if polished, it will tend to have a more matt finish than many plastics. Holding it up to the light should reveal a slight translucence. Process horn (ground horn mixed with adhesive then moulded) may show a ‘pick mark’ on the back where the button was prised from the mould. Horn is heavier than plastic, and smells like burning hair if tested with a hot needle.

Ivory

Ivory is the teeth or tusks of mammals. In button manufacturing, elephant tusks were most commonly used (and sometimes considered ‘true’ ivory), but whale, hippopotamus and walrus teeth/tusks were also used. The material was lathed and carved, and used as a base for painting, scrimshaw or inlay work. Fossil ivory can also used used. This is sourced in Alaska, and can be from mammoths or mastodon.

Ivory buttons are known to have been made in America (by a maker of piano keys) in 1789. In 1812 Arnold Benedict began making bone and ivory buttons in Waterbury, Connecticut.; this became the Waterbury Button Co. in 1849.

Whale tooth button from the National Maritime Museum collection.

In the Victorian era, moves to develop humane alternatives to ivory was one of the reasons materials such as celluloid and bakelite were developed. With dwindling elephant numbers in the wild, there has been a worldwide ban on ivory sales since 1989 (although exceptions were later made).

Sunday Times (Perth), 20th July 1941 page 1.

Leather

Leather is a flexible and durable product made by tanning animal skin/hide, usually cattle but also pig , crocodile, seal, snake and other (and unexpected) animals such as fish!

News (Adelaide), 22nd October 1923 page 5.

The Advertiser (Adelaide), 14th August 1934 page 8.

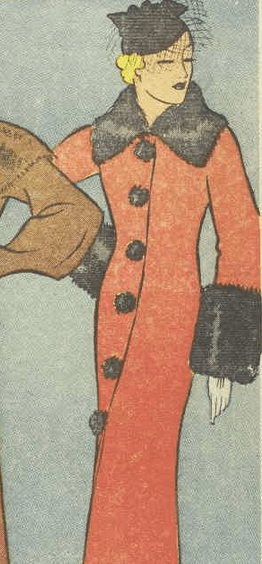

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 25th April 1936 page 8. Black seal skin buttons and collar on a slim fitting red woollen coat.

The making of leather buttons started early on in Australia’s history. An article boasted of various new products being made in the colony of South Australia including …

Adelaide Observer, 15th March 1845 page 6.

Examiner (Launceston), 13th September 1939 page 12.

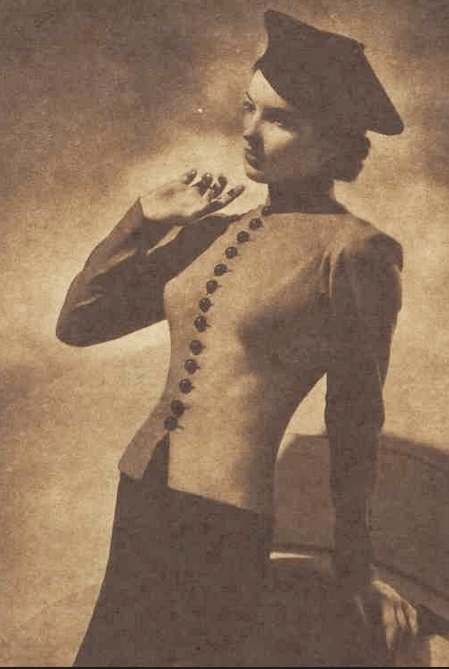

Australian Women’s Weekly, 26th March 1938 page 4. “New ‘sculpted’ jacket blouse by Schiaparelli in viyella. The closely moulded line, stand-up collar, spherical leather buttons, and long hipline are all points of interest.” For more on Schiaparelli see http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/realistics/

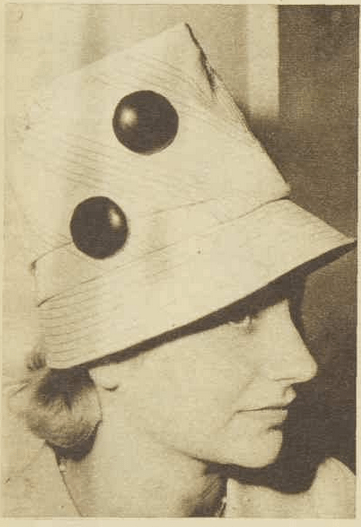

Australian Women’s Weekly, 1st March 1961 page 6. A high crowned white leather hat stitched in black, with two patent-leather buttons.

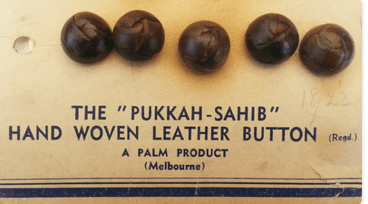

Plaited Leather Buttons

While plaited leather buttons were used before this time, they seem to become more popular after WW2, particularly on sports/tweed coats and jackets, borrowing perhaps from military uniforms. A local industry sprang up to meet the demand. Many European and Jewish immigrants set up in the ‘rag trade’ at this time. Some would use outworkers to hand plait strips of leather into buttons in their homes that would be collected, dyed, varnished and carded to be sold to shops and tailors. They were also made by “crippled children”.

Embossed leather buttons were also made.

Paper

Papier Maché (pulped and/or pressed paper mixed with binders and fillers) was used to make shoe and boot buttons as well as clothing buttons. It could be japanned (varnished with a hard black lacquer), dyed, painted and inlaid. Inlaying of pearl shell onto papier maché dates from the early 19th century although the method was used for buttons from around the mid 18th century.

For shoe buttons, the buttons were soaked in linseed oil or amber varnish. They were then coated with further varnish and baked several times until firm as wood, then polished. They were advertised in Australian newspapers from 1849.

Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld), 4th August 1939 page 10, from a longer article about button manufacture.

Liverpool herald (NSW), 23rd November 1901, page 4.

The Journal (Adelaide), 11th November 1922 page 7.

Other uses of paper for buttons are the rare 18th century French decoupage examples, and painted designs on paper under glass or celluloid. Decoupage buttons are enjoying a revival as craft for quilting.

Pearl Shell Buttons

History

Possibly the oldest shell button found is around 5000 years old from Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley. Some prehistoric examples were carved and pierced so that they could be sewn as ornaments onto clothing.

The banning by the United Kingdom parliament of the importation of pearl buttons in the late 18th century lead to a boom in their production in Birmingham, which was already an established button production centre. Pearl-shell buttons production was labour intensive, with multiple steps (up to 80 for fancy items!) that required a lot of manual handling, even after the introduction of machinery into production. The shell used was imported from Australia, the South Pacific, Malaysia and the Americas. A report in 1866 into the Birmingham button trade included a section on pearl-shell. See https://hammond-turner.com/index.php/component/content/article/14-sample-data-articles/125-the-birmingham-button-trade-part-6?Itemid=435

There was an industry in Europe as shown by the fact that the father of the trade in America, John Frederick Boepple, was an immigrant German button maker with experience in making shell buttons. Due to high importation tariffs , he moved to America in 1887 to avail himself of the plentiful freshwater mussel shells to be harvested from the Mississippi River. Luckily for him, tariffs were introduced in 1890 making pearl shell buttons imported into America expensive. From small beginnings in 1891, a boom industry evolved with a peak of 49 shell button factories and many small backyard units making and supplying blanks. By 1905, Muscatine and neighbouring regions were producing around 37% of the worlds buttons. Muscatine was “the Pearl Button Capital of the World”. Production peaked in 1916, with thousands employed in the industry and millions of dollars earned. However, over harvesting, interruption by WW2, competition from overseas , changing fashions and the rise of plastic contributed to the industry’s decline by the 1950s. Buttons are still made in Muscatine, but nowadays of plastic.

NB: Small amount of stud buttons were made from American fresh water shell from as early as 1802, according to a report of that year. In 1872 fresh water shell may have been sent from Illinois by William Salter to Germany and reached Boepple’s father, although at the time the potential was not realised. They probably were the inspiration for the search Boepple would make some 20 years later.

Shell was exported from Australia from the 1850s until the 1950s to England, America and later, Japan. When Japan was occupied after WW2 from 1945-1952, General Douglas MacArthur was entrusted to revive Japan’s economy. Buttons were among the products made and exported to the world. The words “Occupied Japan” or “Made in Occupied Japan” were required to be printed on products.

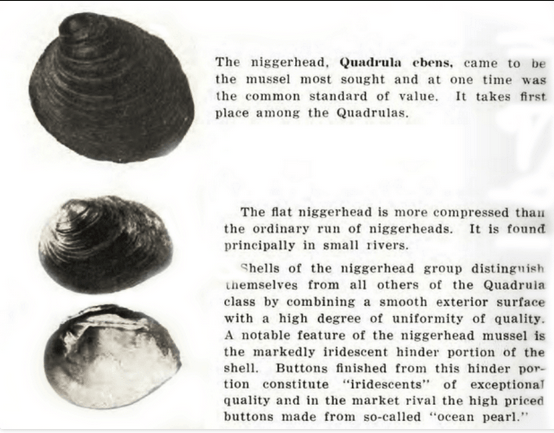

Fresh water shells were imported to Germany until WW2. Quoting from the B.I.O.S. report dated 1/1/1947 about the factory of Franz Muller, Amorbach in Bavaria: “The stock of shells was found to be very large, the estimated weight being 50 tons. The type of shell was Mississippi Sand Shells and Nigger Heads.”

From “Our Pearl Buttons” by E. P. Churchill, in The Companion For All the Family, 26th July 1923.

Australian shell was also exported to Israel for the production of exquisite, hand-carved, “Bethlehem Pearl Buttons”. The production of shell buttons in Australia occurred intermittently from 1880, but was never significant. See the Pearl Sell page of this blog for more on this topic. According to the British Shell Club, pearl buttons are being produced today in America, China, Indian, Japan and the Philippines from a variety of species.

Japan started importing shell buttons in the last quarter of the 19th century, then gradually an industry centred around Osaka grew up. By 1907 there were around 70 factories there, with exports to India and China occuring. Trocas was a main material.

http://www.astonbrook-through-astonmanor.co.uk/pearl_buttons.html

http://uipress.lib.uiowa.edu/bdi/DetailsPage.aspx?id=38

https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/pearls/freshwater-pearls/button-capital-of-the-world

https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7813&context=annals-of-iowa

Dating USA shell buttons

It is not always easy to date these buttons, but the cards can help. Some actually have a copyright date printed on them. Knowledge of when a given company existed can give you the era. You might notice that on some cards the buttons are attached by staples, or in the case of the shanked buttons, a fine strand of wire threaded through the shanks behind the card. By looking at many cards of many eras, I suspect this occurred from the 1940s in America, with cards before then having sewn on buttons. In Australia staples were not used until the mid 1960s, and even until the 1980s many buttons were sewn onto cards. Cards of pearl buttons marked “Made in Occupied Japan” (i.e. 1945-1952) show that during that era the style number, size in lignes and sometime quantity of buttons per card (in case you couldn’t count?) were printed on the card. This was also the era that prices started to be printed (around 10-15 cents per card.)

According to The Daily Gazette (new York) in 2017, “Harvey Chalmers & Sons made a splash in the industry in 1911 when it was the first button maker to advertise in women’s magazines and newspapers. The company became the biggest manufacturer of pearl buttons in the world with sales offices in New York and London.”

Copy of the 1911 ad.

One of the cards.

Plastics

See http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/australian-button-history/federation-to-ww2/#PLASTICS

Identifying one plastic from another is difficult without a handy gas spectrometer, and many plastics are chameleons, able to mimic other materials as well as each other. A useful guide to plastic identification is http://www.buttonimages.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/identifying.pdf

The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW), 22nd July 1942 page 8.

Bakelite/Catalin

Bakelite, or polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride, was the first synthetic plastic. It was developed in 1907 by Dr Leo Baekeland working on a substitute for shellac, and patented in 1909. It was made from phenol and formaldehyde with added fillers such as wood or asbestos fibres. As a result, mainly dark, sombre colours were made to cover up the appearance of the fillers. According to ‘An insight into Plastics’ by BTR Nylex Ltd., the plastics industry started in Australia around 1917 with buttons moulded from imported phenol-formaldehyde powder being among the first products manufactured.* Moulded Plastics (Australasia) Pty. Ltd. made ‘Duperite’ products from 1932. These included buttons for the Australian Military Forces between 1940-44.

*Editor’s note: The first buttons were moulded in 1917 by Frederick Spencer Dalton, who made compression moulded buttons of phenolic powder for great-coat buttons during WW1.

In 1925 the British Cyanides Company (whose trademark was a beetle) developed a thiourea-formaldehyde moulding powder which was marketed from 1928 as Beetle powder. In Australia, Duperite branded products, and others, were made from this imported powder. This type of plastic allowed the introduction of previously unavailable colours, and are mottled or marbled.

In 1927 the American Catalin Corporation of New York City acquired the patents for Bakelite and developed Catalin plastic. Catalin is what most “Bakelite” jewellery is actually made of. It was also made from phenol-formaldehyde, but in a 2 stage process without the use of fillers. It was available in clear and solid colours, as well as light, bright options that were not possible with Bakelite. It oxidises over time so that clear and white objects will yellow.

Casein/Galalith/Erinoid/artificial horn.

Formaldehyde was also used with casein protein from milk to make a plastic. An early form, Lactoform, was produced in 1895 by two German scientists. The first French/German version, called Galalith (meaning milk stone), was developed from 1899 and patented in 1906. It was successfully made in England from 1914 under the name Erinoid. Production slowed during the war as milk was needed for food. Casein was favoured for button production because it wasn’t flammable like celluloid and could be produced in many colours. It also polished up to a beautiful luster. In 1931 O. C. Rheuben & Co. (formed from the previous Herrman Co.) were described as manufactures of casein buttons. (It is possible Herrman had produced casein buttons as early as 1919.) In 1935 at the North Coast National Exhibition, casein buttons, products of Norco, were displayed. In the collection of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, is a casein formaldehyde button made in 1944 by General Plastics.

The Pemberton Post (WA), 5th November 1937 page 5.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 10th May 1939 page 12. From an article discussing the effect of the embargo on Germany’s trade during the war.

Erinoid buttons and buckles were advertised in Australia around 1937-49. The term galalith was used from 1913-1939.

The production of casein plastic was revived after WW2, but would decline in the face of newer plastics that were easier and cheaper to make. The last French company, Establissements Feuillant, closed in 1981. They had been making Galalith since 1947.

http://www.schoenlaub-galalith.com/galalith/

https://www.galalith.store/about

Hemacite

Melbourne Punch, 6th October 1887 page 5.

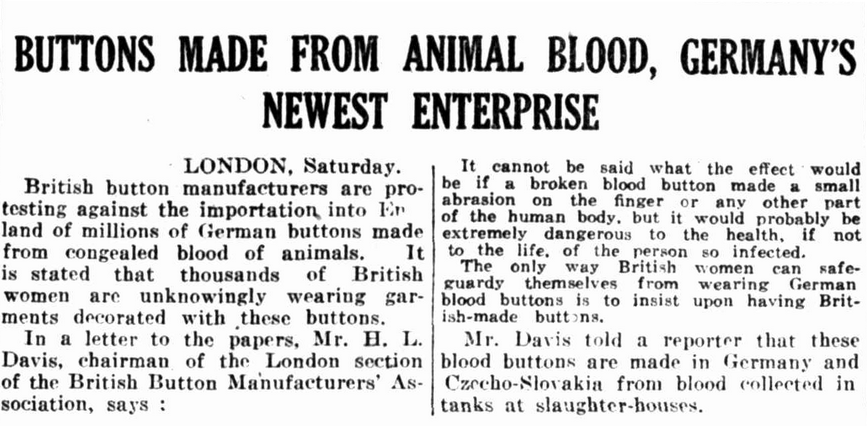

Sunday Times (Sydney), 23rd May 1926 page 3. The blood buttons were unlikely to be a source of infection, as they were baked at high temperatures. This was probably just an attempt to make shoppers ‘buy British”.

According to Wikipedia: Hemacite was an pre-plastic made from sawdust and the blood of slaughtered animals treated with chemicals and pressure. It was invented by Dr W. H. Dibble of New Jersey in the late 19th century, and was widely used.

According to the magazine “Just Buttons” published in August 1944, buttons from dried blood were made on an industrial scale in Saxonia, Germany, prior to WW1. A factory existed for a short time after the war in Western Germany. The buttons were black or dark colours, and although attractive, brittle and affected by moisture. A couple of factories manufactured blood buttons in Rochester and New Jersey, USA, but both found the method too expensive to be profitable.

Hemacite rollers for rollers skates were advertised in Australia from 1888-1914.

Irridel

If you’ve perused the vintage Beutron advertising, you’ll remember that In the late 1940’s they marketed ‘Irridel’ buttons that matched the colour of lighter or darker fabric due to their opalescent nature. A newspaper article showed the origin of this type of plastic;

The Argus (Melbourne) 9th December 1939 page 17.

So, many years before Beutron used the name, Irridel was a type of American plastic used to make jewellery. Beutron imported the formula to Australia to make the buttons. The name borrows from the earlier “Iridill”, the name of a type of glass produced by the Fenton Art Glass Company from 1908. This was the glass that became known as ‘Carnival glass’. It was a very successful product for Fenton, with popularity peaking in the 1920’s and waning into the 1930s. For all its fancy name, this plastic was a type of casein.

Lucite

A useful plastic for making buttons is polymethyl methacrylate, better known by the trade names of Lucite, Perspex, Plexiglas, Acrylite, and others, but more easily referred to just as ‘acrylic’.

Developed in the 1920s and first marketed in the 1930s by several companies, it would be widely used during WW2 for airplane turrets, windscreen and the like. Du Pont had licensed this new product to jewellery manufacturers early on, which is why the name Lucite (their trade name) is used generically for acrylic buttons. It proved a valuable and flexible product, highly suitable for the manufacture of jewellery, beads, buttons and many other products. Although naturally clear, it could be made coloured, translucent or opaque. It was lighter than glass, strong, and did not yellow with age (unlike bakelite/catalin). Its peak popularity was post WW2 through into the 1960s, although it is still used. Vintage plastics with embedded glitter or other objects are usually acrylic. I have buttons of the ‘Moonstone’ acrylic variety, with a slightly greasy feel and a glossy, glowing, variable colour tone.

The Herald, 24th September 1946 page 9. A three quarter coat featuring “big Perspex Ice buttons – so beautiful, new, arresting!”

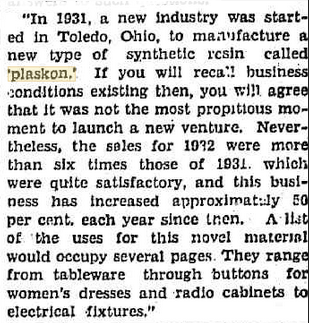

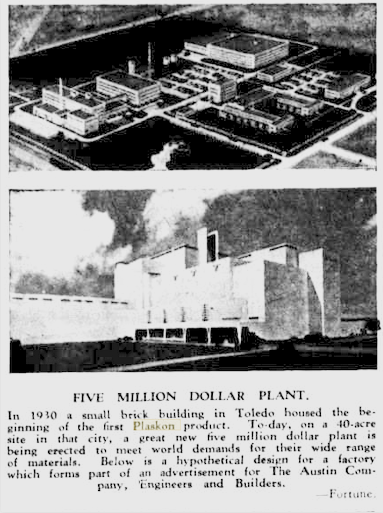

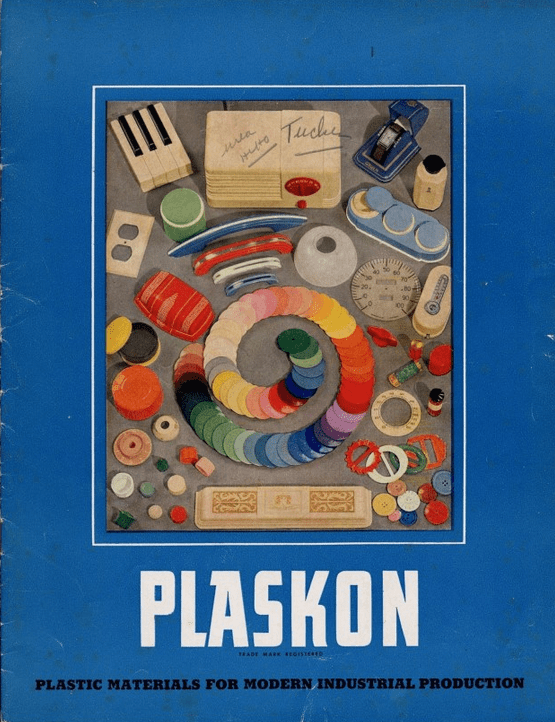

Plaskon

Plaskon was developed in 1931 by the Toledo Scale Company as a lighter material than metal to make their scales from. It was made from urea formaldehyde with cellulose as a filler, as was great for making white products.

From my Lansig catalogues, a Plaskon button.

Warwick Daily News(Qld), 31st December 1936 page 2.

Construction (Sydney) 7th January 1948 page 4.

NMAH Archives Center J. Harry Dubois Collection, 1900-1975. These buckles and buttons in the bottom right corner make me think that many of my old plastic buttons could be Plaskon.

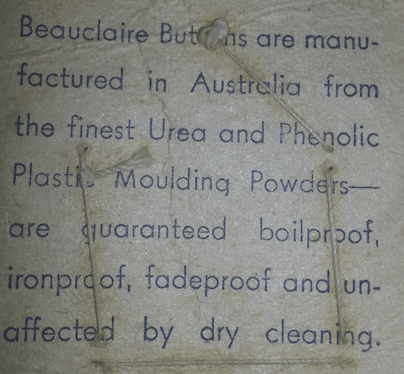

This was printed on the back of early Beauclaire branded cards, so dates c.1951. It indicates that their buttons at that time were Plaskon (or similar) and Bakelite (or more accurately Catalin).

For more about Beetle powder: http://plastiquarian.com/?page_id=14240

Polyester

According to https://www.popoptiq.com/types-of-buttons

“Polyester is a very common material for buttons because it is a type of plastic that makes it perfect for all types of buttons. Polyester is inexpensive, looks great, and can be dyed a variety of colors. Sometimes, red carbonate is added to polyester to make buttons that have the pearlescent sheen of shell buttons, but the truth is, polyester buttons offer so many options that it is all but impossible not to find something you love when you choose buttons made of this material.

Polyester buttons make it easy to button and unbutton a dress or blouse, and if you choose polyester buttons, they can even mimic other button materials, which means you are always guaranteed to get what you love without paying a fortune. Polyester buttons can be made to look like wood, pearl, or any other type of button, thanks to their versatility and the fact that they come in so many designs and colors.

For most non-professionals, therefore, it is virtually impossible to look at a button and determine whether it is made of polyester, wood, or any other type of button-making material. Most polyester buttons vary greatly when it comes to shading, luster, and brightness, so they can be light or dark, formal or casual, large or small, meaning you are always guaranteed to get something spectacular in the end.”

The term ”polyester” most commonly refers to a plastic sub-type called polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Wikipedia tells me that polyesters are a family of plastics that can be both themosetting or thermoplastic, which doesn’t help with hot needle testing.

According to an article in the Pioneer Button Club, July 2018, polyester has taken over from acrylics for high end buttons being produced today. The author also bemoaned the lack of a “foolproof, non-destructive way to tell acrylic from polyester 100% of the time.”

Eurobuttons (manufacturing in Bulgaria) state that polyester buttons “are the most used in the world because they offer high quality at a low cost”.

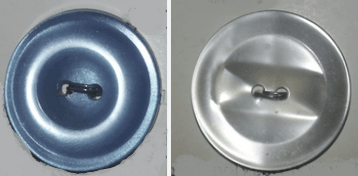

Polystrene

In the post war period, polystyrene buttons had proved disappointing and were banned by the American Drycleaners in 1947.

South Western Times, 2nd September 1954 page 7. Mr Smith was a West Australian dry-cleaner who had attended a national conference where “the button issue” was discussed.

Potato (Anras) buttons

Early pre-plastics (a.k.a. “artificial horn”) were being developed from vegetables such as potatoes, turnips and carrots in 1867. They were soaked in acid then clear water before drying, colouring, carving and polishing.

The Queenslander, 5th December 1891 page 1083.

The Sunday Times (Sydney) 11th March 1906 page 6.

From the 1947 ”German Button Industry” BIOS report:

” A considerable stock of Anras Sheet material was found which was a Casein substitute material made from potato starch by Messrs. Anras Combine at Veendam. Production of Anras buttons was similar to normal Casein production but the material was very hard and could not be polished with a chemical polish.” The report then details how both Casein and Anras buttons were polished in five stages that took 4-6 days!

Raffia

Raffia is made from the leaves of the raffia palm, which are harvested, stripped then dried. It is easy to dye, strong and pliable, making it a good material for plaiting. Victour Houart, in his “Buttons. A Collector’s Guide” book of 1977 claimed raffia buttons were made in Germany from the 19th century until WW2.

The Sun (Sydney), 28th July 1935 page 37.

The Bulletin, 8th May 1913 page 24.

Australian Women’s Weekly, 6th May 1953 page 53.

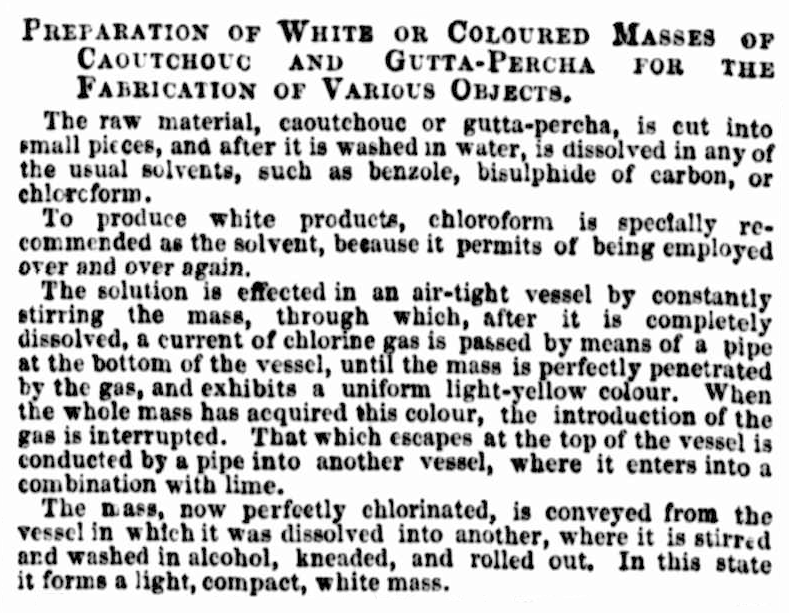

Rubber

Rubber is derived from the Amazon rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Several types of rubber have been used to make buttons; vulcanised (Goodyear), gutta percha, and compositions. Rubber buttons were made under licence to Goodyear from around 1854-1898. They are mostly black, but also brown and red.

Gutta Percha is made from latex obtained from the leaves and bark of certain trees (Gutta Percha tree of the genus Palaquium family Sapotaceae) It needs to be noted that all ‘gutta percha’ items contain rubber and/or other materials as it was not used in isolation.

Kapunda Herald (SA), 5th August 1890, page 4.

Sydney Mail, 23rd June 1866 page 8.

Northern Star (Lismore NSW), 28th January 1931 p10. Described as occurring in cream and colours, this must be some kind of synthetic rubber.

Seaweed

Buttons were made from a brown seaweed called lamaniaria.

The Maitland Weekly Mercury (NSW), 17th October 1925 page 9.

The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser, 15th January 1934 page 1.

Shell (apart from pearl-shell)

Cowrie, pinna, trochus and abalone (paua) and other sea-snail shells have been used for button making due their beautiful colours and pattern. As well, whole shells have sometimes been used as novelty buttons.

Coolgardie Miner (WA), 15th July 1937 page 5.

The Sun (Sydney), 26th December 1938 page 7.

For more on trochus: http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/uncategorized/9466/

Turtle/Tortoise Shell

In the past buttons and other items were made or decorated with a now outlawed form of modified bone; turtle shell, particularly from the hawksbill turtle. It was much prized for its colour and ability to take a high polish. It was used as a veneer on other materials, or as a base for inlaid work.

Detail of advertisement for fancy goods: Sydney Morning Herald, 8th June 1877 page 7.

Rockhampton Bulletin (Qld), 13th February 1874 page 3.

https://australian.museum/learn/animals/reptiles/hawksbill-sea-turtle/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tortoiseshell

Wood (including nuts and bark)

Burwood/Syroco

In America several companies developed a way to make household novelty products, including buttons, from wooden composition material that could be easily moulded. This saved the time and expense needed for hand carving. These include Syroco, Burwood, ANN and GAP. However, according to “The Big Book of Buttons”, the origins go back to the 1850s when hardened wood (bois dura) buttons were made in France. These consisted of sawdust and albumen, coloured bronze or jet black, with the buttons usually decorated with cameo style heads. Then in the 1880s, during the craze for metal picture buttons, several manufacturers made picture buttons of pressed or moulded wood composition. The composition was made from pulped or powered wood with fillers and binders. You could achieve more detailed designs with this material than by pressing designs on wood. Albert Parent and Company made good quality buttons of this type. They have a metal back plate marked with the company name (AP&C Paris).

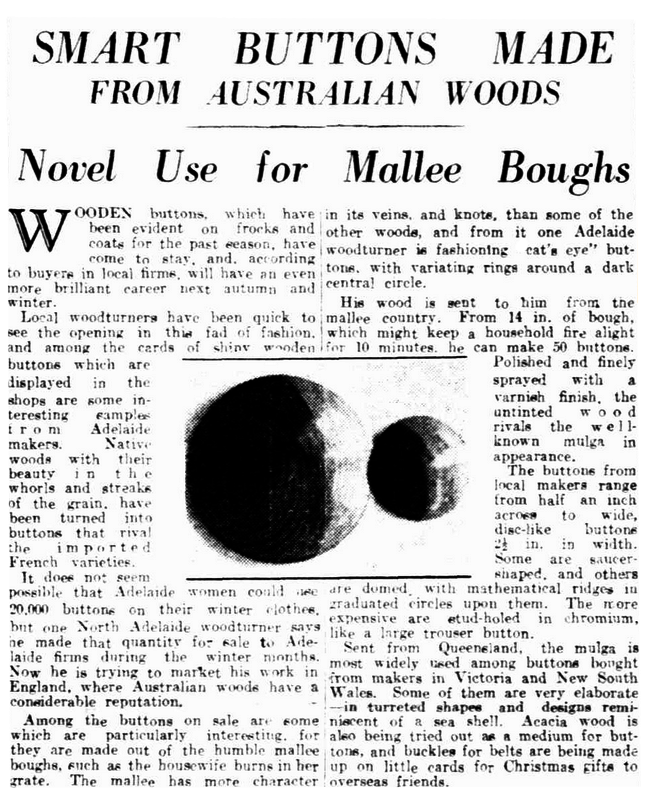

The Inverell Times (NSW), 10th June 1935 page 6.

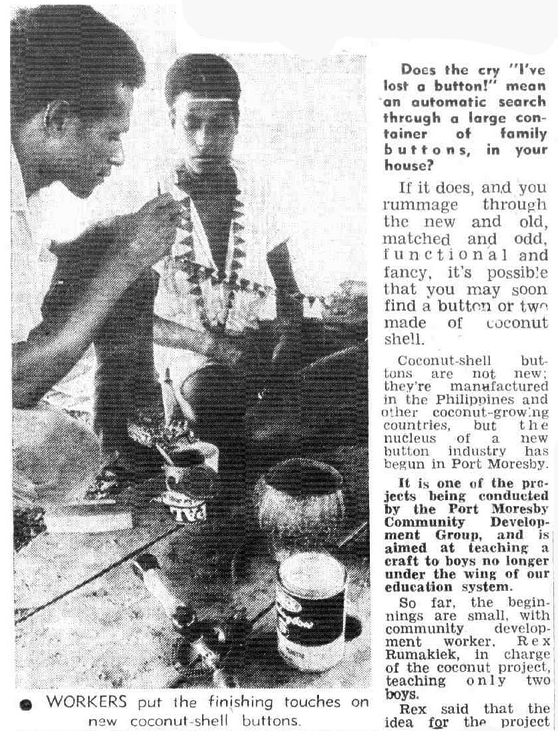

Coconut Shell

The Tribune (Philippines), 8th May 1934 page 10.

The Tribune (Philippines), 23rd June 1937 page 1.

The Broadcaster (NSW), 17th September 1936 page 2.

The Dubbo Liberal (NSW), 19th June 1941 page 6.

Papua New Guinea Post-Courier, 5th January 1972 page 19.

Nuts/kernels

The Inverness Times (NSW), 21st January 1935 page 6.

The Daily telegraph (Sydney) 16th October 1935 page 10.

News (Adelaide), 25th October 1933 page 10.

Australian Women’s Weekly 18th March 1950 page 60: A young Hungarian migrant living in a migrant’s camp made these buttons and necklaces from plum and cherry stones and walnut kernels and shells, carved by knife.

The earliest mention of these I have found was a description of a groom’s clothing in 1890. These nuts were favoured as a durable, readily accessible, free material by country folk, but were also regarded as very attractive.

From the cover of the February 2008 issue of the Button Collector magazine.

Western Mail (Perth), 12th December 1935 page 46. If Frank, whoever he was, doesn’t want the buttons, I’ll have them!

Some readers answered below:

The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 24th December 1939 page 15.

The Bulletin, 2nd October 1940 page 17.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 5th May 1954, page 13. It appears quandong seeds were used for DYI buttons reaching back into the 19th century, but faded out in the 1930s. According to a story in the Chronicle in 1940, there had been (?when) a horse breaker in New South Wales known as Quandong Ned as all his buttons were made from Quandong seeds. The seeds were cut in half and holes were bored with a hot wire or a boring tool. He also used the seeds instead of cork suspended from the brim of his hat.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 16th December 1911 page 12.

Western Mail (Perth), 23rd February 1922 page 19.

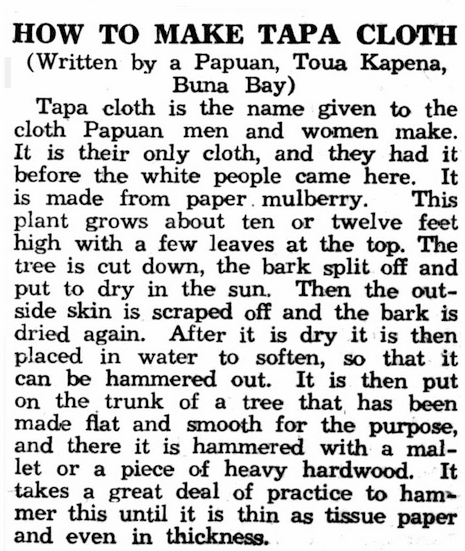

Tapa Cloth

This cloth was made from the soft inner bark of the paper mulberry tree from Pacific islands. Some buttons were made that were covered with this material.

The Methodist (Sydney), 20th May 1944 page 11.