Table of Contents

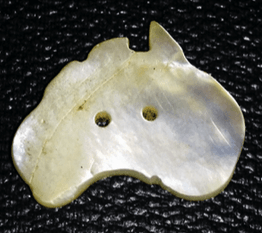

The Australian pearling industry started in the 1850s at Shark Bay, West Australia, then in Torres Straits in 1868. Sixteen firms were operating from Thursday Island by 1877, and nearly 400 luggers plus more than 3500 people fishing for shell in the waters off Broome by 1910. In 1890 the Torres Strait was supplying over half the world’s demand for pearl shell. The shell was sold in large quantities to England and America, and later Japan, for the manufacture of buttons and buckles. It was worth anywhere between 79 to 400 pounds a ton. This created a boom time for the pearling areas with large numbers of European, Asian, Islander, Koorie and Chinese people arriving to work in the industry. This in turn had a terrible effect on local islander populations with up to a 50% reduction in population from 1870 to 1900.

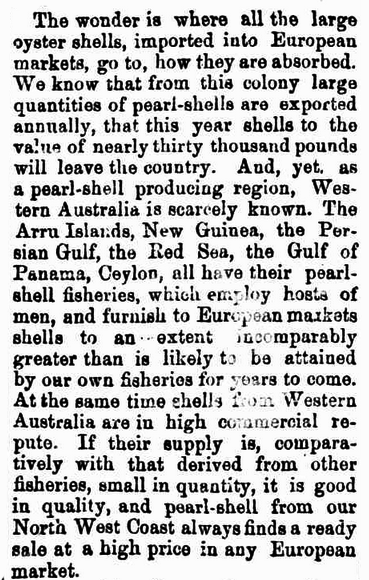

The Herald (Fremantle), 31st May 1873 page 3.

The industry relied on exploitation. At Shark Bay aboriginal people were forced to work, even kidnapped, (a.k.a. “blackbirded”) without wages to collect shell. Later they were required to dive without equipment into deep waters for shell. The working conditions were very poor and dangerous. Once diving suits were invented, divers, who were often Japanese indentured workers, were required to spend hours at a time under water with danger from shark attack, poor weather and the ‘bends’. The mortality rate may have been as high as 50% for divers.

Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney) 29th February 1896 page 26. Thursday Island: Diver in full dress.

Kalgoorlie Western Argus, 27th April 1909 page 23. Cleaning shell.

After Federation, the ‘White Australia Policy’ restricted the immigration of cheap and ‘expendable’ divers. In 1912 twelve British ex-navy divers brought out to work in the industry at Broome. However, after the death of one, the paralysis of another and a bad case of “the bends” in a third, all withdrew from the pearling fleet. After this, Broome was made an exception to the ‘White Australia’ policy.

Sunday Times (NSW) 3rd October 1920 page 18. Luggers laid up for the off season.

The Daily News (Perth) 16th June 1926 page 8.

The industry almost stopped during World War 1, as its workers enlisted and shell prices crashed. Most pearling vessels lay idle.

There were other pressures on the industry. As early as 1934, an overseas expert was warning that shell prices were dropping due to reduced demand. Fresh water shell, trochus shell and casein were in competition for use in button manufacturing, with casein being considerably cheaper. Despite the hopes of politicians and “pearlers”, previous over-harvesting as well as high production costs slowed recovery of the industry after the war. There were issues with availability of divers: some wanted to reduce the use of ‘foreign’ divers, whilst others were claiming the industry was reliant on them. During the 1950s plastic buttons and buckles largely replaced those made of pearl shell. A new pearling industry would evolve based on cultured pearls with pearl-shell as a side-line; the opposite to what happened historically, where pearls had been the side-line.

Sydney Mail, 20th February 1935 page 34.

The Australian Woman’s Mirror, 10th September 1929 page 13.

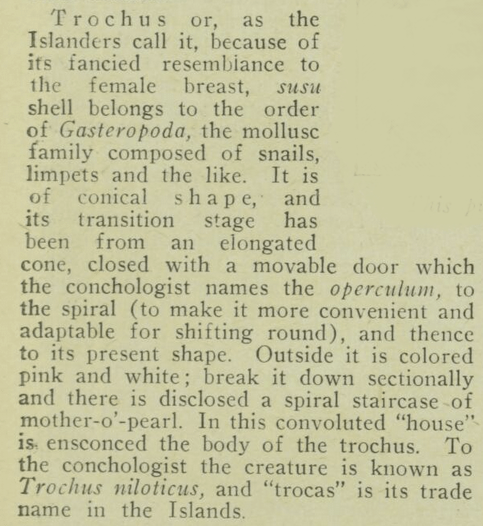

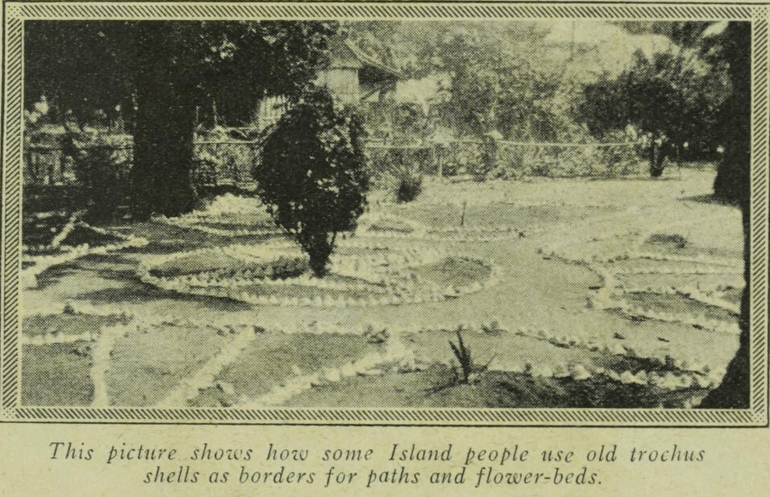

Weekly Times, 8th may 1937 page 46: Trochus shell.

1964 Weet-Bix trading/collecting card.

See http://www.austbuttonhistory.com/uncategorized/9466/ for more about the trochus shell industry.

Mirror, 10th March 1931.

History of Attempted Local Pearlshell Button Industry and Tariffs

As early as the 1880s there were several small scale attempts to start pearl stud and button factories in Sydney, but a lack of experienced workers was a problem. These attempts lasted up to several years in duration.

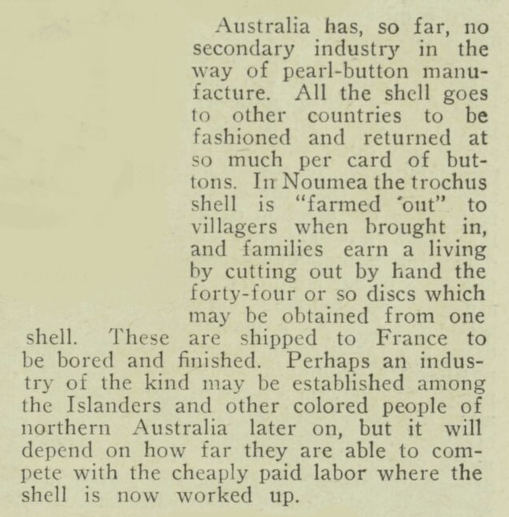

Around 1906, with the shelling industry suffering the effects of depletion of stock in the shallower waters of Torres Straits, there were calls for a local processing industry to help support the industry. Places suggested included Sydney, Brisbane, Broome, Darwin and Perth. Unfortunately, many proponents of the idea were writers, scientists, or parties with vested interests such as pearlers, unions and local politicians, not economists or experienced button factory owners. The proponents claimed things such as ” the factory would be a great success, for … the Commonwealth would be able to manufacture at a far less cost (than those) who have to first import their shell”, which was simply not true. It was also claimed that the plant was “not at all expensive”, and pointed to places such as New Caledonia where such a factory existed. Whilst the plant, in the pre-automated days, may have been inexpensive, it would still have required some expense to import it, and to train staff. There was also the fact that labour costs were relatively low in places where the industry prospered. For example, in Britain and America (where the industry was successful) workers’ advocates complained that workers, including women and children, worked long, lowly paid hours in the button factories. Tellingly, the proponents always suggested, or demanded, or pleaded, that the Government should subsidy the setting up of such a factory, overlooking the fact that if it were likely to be profitable, private industry would do so without government help.

The shell harvesting industry crashed during WW1 as the labour force left to enlist, and shell prices dropped. Post war, the industry rebuilt and prices for shell rose again. The shell button industry was suggested as a means to provide employment to the injured soldier, who could “also receive buttons to mount on cards at home … at his leisure.” A Government grant from the Repatriation scheme was suggested to start this.

The Great Depression caused a ‘National Emergency’ to be declared in 1929. To try to protect local industry, import tariffs were raised. The following year, further taxes were imposed on ‘luxury items’, which included buttons. A series of inquires into altering tariffs started in August that year. In September they considered buttons, buckles, claps and slides. O. C. Rheuben, of the Herrman Company, claimed the change proposed would cover £150,000 of the £500,00 worth of these articles being imported in 1930 duty free. He claimed that in consequence he could increase his employees up from 22 part time, to 120 workers. The changes to the relevant tariffs were approved. A year later the firm’s output had increased by 400%, and a German engineer was coming out to oversee the installation of new machinery.

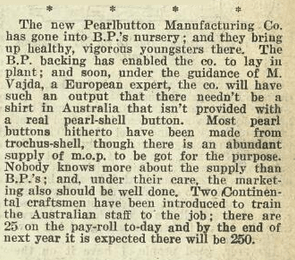

In 1929 two or four (depending on which report you read) Viennese experts came to Australia to help start the ‘Australian Pearlbutton Manufacturing Co. Ltd.’ This started production on the 1st May 1931 with 24 hands. This enterprise by the firm Burns Philp & Co. was apparently encouraged by the Federal Government.

Pacific Islands Monthly, 19th June 1931, page 4.

The Bulletin, 22nd July 1931 page 17. BP stands for Burns Philp.

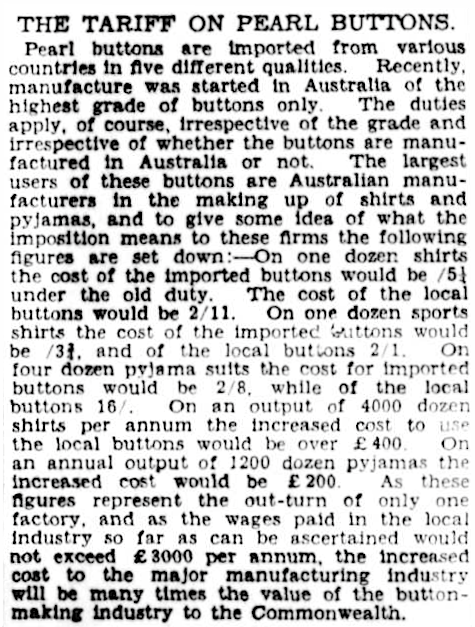

By 1932 it was employing eighty people. However, the tariff protecting the industry was claimed to be effectively 1100%. The Sydney Chamber of Commerce estimated this would cost approximately £25,000 annually to the Sydney shirt and pyjama makers, the main consumers of pearl-shell buttons. They said the industry was “ill-conceived” with claims that 500 people could be employed “ridiculous”. At that time most shell buttons consumed in Sydney were made in Japan from Australian trochus shell, so that to stop importing Japanese buttons in favour of locally made would therefor cause loss to the shell exporters. They were also concerned about the possibility of retaliation by Japan in reducing importation of Australian produce such as wool.

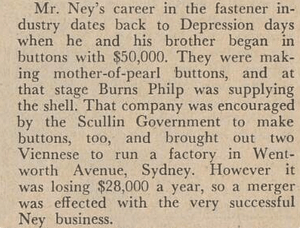

In 1932 a Northern Territory politician insisted that a “properly protected” industry could supply 80% of the world’s finished product. An opposing politician claimed that he was told “a German came to Australia with a proposition to make buttons. A company (Burns Philp) fell for it and financed him. His backers were now trying to use the tariff to recover their losses.” Although this was possibly just gossip, it is true that by 1938,despite a 15-25% tariff on pearl-shell buttons the Pearlshell Company was in liquidation, losing £28,000 per year. It would be merged with the successful enterprise, G. Herring Pty Ltd. which was run by the Ney brothers, Marshall and Cornelius.

By 1935 there were apparently 3 pearl-shell factories in Sydney; PearlButton Manufacturing Co, G. Herring, and Pearl Products Manufacturing Company, one of these employing only four people. Herrman & Co was possibly the company referred to in a statement by a shell expert dated 1935: “ … some years ago a company was formed in Sydney to manufacture buttons. The quality was excellent but the costs of production uncompetitive … recently it turned its attention to manufacturing composition buttons.”

As early as 1909 a newspaper reported the production of “mock pearl buttons” made from milk. The plastic industry had been growing before WW2, and by the 1950s was booming. It was reported in 1951 that MOP exports had steadily earned less since 1948 (1948: £558,000 c.f. 1951: £198,000). Due to low production and the high prices of shell buttons since the war synthetic button manufacturers in the US had captured the market. Despite that, on the 8th March that year ‘Pearl Shell Industries Pty. Ltd’ was formed at Smith’s Creek, near Cairns, primarily to make buttons. A. G. R. Griffths, managing director of General Plastics Pty Ltd, was one of the directors. Fully automatic plant had been ordered from New York costing many thousands of pounds. General Plastics was to perform the rumbling and chemical polishing, as well as the sale and distribution of the buttons. In November of 1953 the Cairns factory had reportedly more equipment on the way from Germany. Unfortunately, the era of pearl-shell buttons was nearly over and the business went into liquidation in 1954. It survived with another owner only until around 1956.

In September 1953, a MOP manufacturing plant, with a foreman and 9 operatives, was being advertised for sale as a going concern with profits of £40-60 per week. Apparently the space was required for extensions by the seller. The advertisement didn’t state who the company was or where they were located.

Despite all this, local unionists were still “demanding” a shell processing factory to provide employment and cheaper articles! According to a 1958 Tariff report, local production of pearl buttons had ceased and about 90 percent of the previous demand was now met by imitations.

Manufacturers

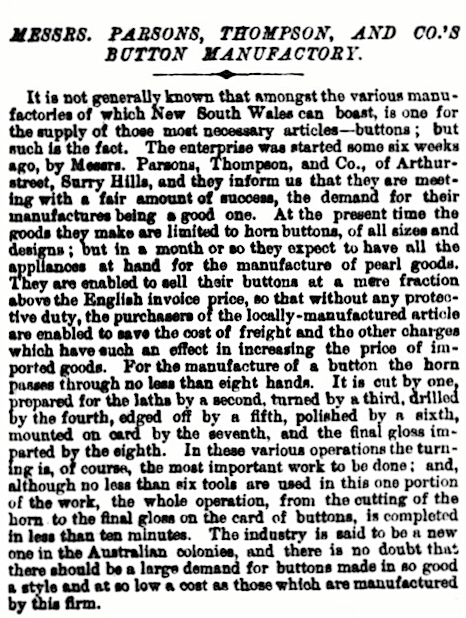

Parsons, Thompson, and Co, Sydney

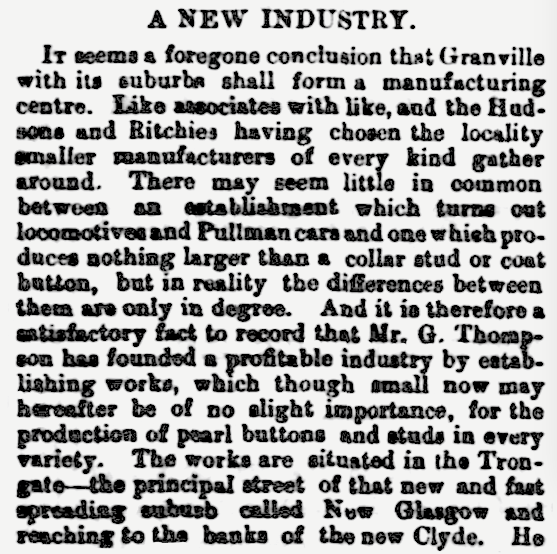

Sydney Morning Herald, 10th February, 1881 page 8.

The Goulburn Herald and Chronicle, 14th February 1881 page 2.

“Mr Parsons” was likely Charles Tilbury Parsons, who lived in Surry Hills at that time. He would leave Sydney for Gosford, with the firm becoming Messrs. Thompson & Co. Mr George Simeon Thompson (1852-1938) moved to Granville (See article below.) He was only located there for some months, as later in the year he had moved back to Sydney. He must have continued for some years, as he was advertising his pearl shell studs and buttons in Melbourne in 1889.

The Cumberland Mercury, 25th April 1885, page 8.

Jewish Herald, 26th April 1889 pages 5 & 12.

There is a collection presented by Mrs J. Fagen to the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences that may be linked to Thompson & Co. (due to the quoted date of 1885). Alternatively, it may be linked to Mr Ackman of Bennetts Chambers, Sydney (see story below).

https://collection.maas.museum/object/21

https://collection.maas.museum/object/15

https://collection.maas.museum/object/19

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228451

The Sydney Morning Herald, 27th February 1886 page 16. This may be the donor’s husband, and would explain why she possessed button drilling equipment.

Mr. Ackman, Bennetts Chambers, Sydney

Mr Samuel Ackman (or Ackmann) was a London born business man. He started as a storekeeper in Melbourne, was for a time a money lender in Ballarat, then moved to Sydney around 1875 to run an auctioneers firm ‘Harris and Ackmann’, amongst many other activities! Around 1879 (according to newspaper reports) he established a pearl button and stud factory. He died in 1922, aged 78 years.

Evening News (Sydney) 12th March 1886 page 3.

Sydney Morning Herald, 2nd Aug 1886 page 7.

John Ward, Brisbane

Another early manufacturer was John Ward from Birmingham with years of experience in MOP trade, who operated in Brisbane from at least 1884 to 1889. He used Torres Strait shell to make studs, links, fancy and dress buttons.

The Telegraph (Brisbane), 11th October 1884 page 5.

The Telegraph (Brisbane), 13th May 1889 page 3.

Australian Button Industry Ltd.

This button manufacturing business never eventuated.

The Bulletin, 7th December 1922 page 14.

Australian Pearlbutton Manufacturing Co. Ltd./G. Herring Pty. Ltd.

The establishment of a pearl button industry here was hampered by a lack of local expertise. In 1929 two or four (reports vary) Viennese experts came to Australia to help start the ‘Australian Pearlbutton Manufacturing Co. Ltd.’ at 16 Foster Street, Surry Hills, Sydney. It was also referred to just as the ‘Pearlbutton Manufacturing Co.’

Newcastle Morning Herald, 13th June 1931 page 14.

16-28 Foster Street, Surry Hills. The button factory did not occupy the whole building.

This enterprise by Burns Philip was encouraged by the Federal Government. By 1931 it was employing 40 people and by 1932, eighty people. In 1935 it was also listed at 297 Rae Street, North Fitzroy, Melbourne.

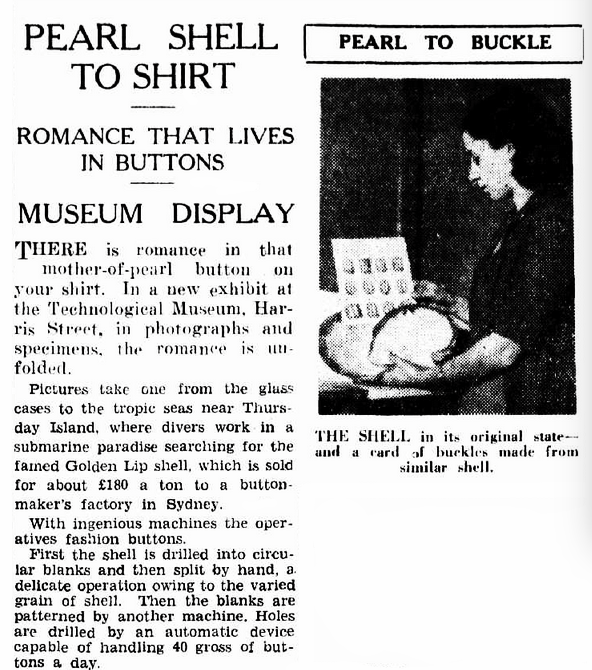

In 1931 The Technological Museum (which became MAAS) held an exhibition of the pearl-shell industry:

The Daily Telegraph, 2nd June 1933 page 8. The exhibition was donated to the museum in 1933 by the company.

For images of this company’s products donated to the MAAS in 1933 see:

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228478

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228477

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228511

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228473

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228476

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228518

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228454

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228474

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228468

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228464

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228458

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228475

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228466

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228508

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228453

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228479

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228461

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228465

https://collection.maas.museum/object/228480

The company applied successfully for increased duties on imported pearl buttons, much to the dismay of clothing manufacturers, who claimed that “only pearl-shell buttons suitable for use in the finishing of high class goods” were being made locally, not the cheaper ones needed for “working shirts, cheap pyjamas, and similar goods” They were faced with higher costs in manufacturing clothing to protect the infant pearl button industry. Despite the tariff, by 1938 the company was in liquidation. It was bought and merged into ‘G.Herring (Aust.) Pty. Ltd.’

The Sydney Morning Herald, 24th June 1931, page 13.

The Bulletin, 21st September, 1968 page 46.

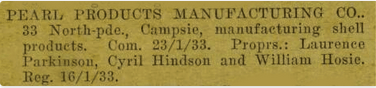

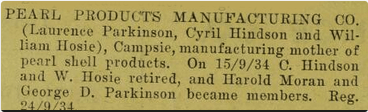

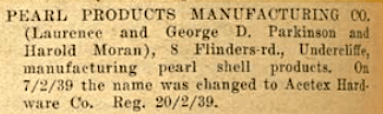

Pearl Products Manufacturing Co., Campsie

This company was registered on 16th January 1933 at 33 North Parade, but changed its name to Actex Hardware Co. and moved to Undercliffe on 20th February 1939.

Dun’s Gazette for NSW, 1933.

Dun’s Gazette for NSW, 1934

Dun’s Gazette for NSW, 1939.

Laurence Ryder Parkinson (1915-2008) was a manufacturer. His initial partners were Cyril Alleyne Hindson ( 1912-2004) and William Hosie, who both left the business by September the next year. They were replaced by Laurence’s father, George Dobson Parkinson (1885-1948), a builder, and Harold Moran. As the name change suggests, the company produced hardware, at first plastic then later metal as well, such and door handles. By 1967 they were known as Acetex-Goal. The company is deregistered.

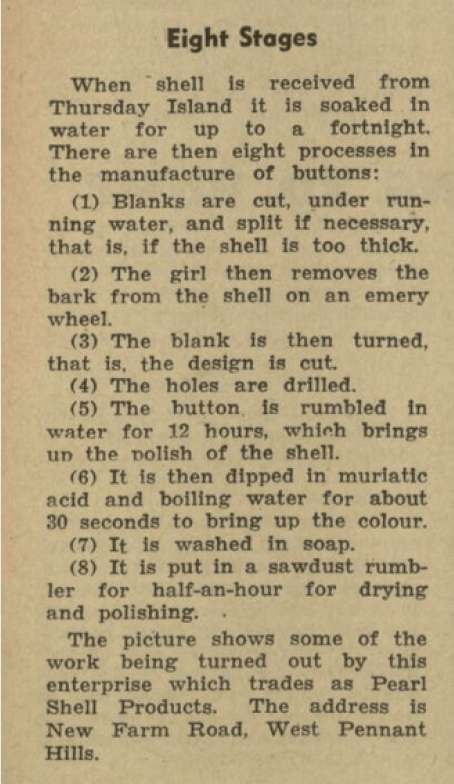

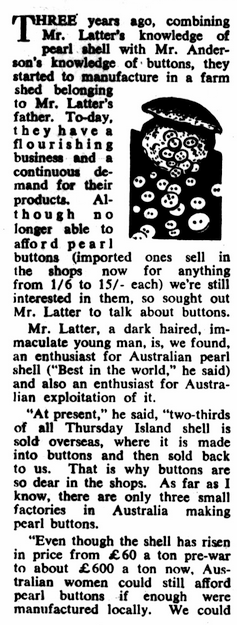

Pearl Shell Products, Sydney

Dun’s Gazette for NSW, 1947.

Malaby Chappell, Cleveland William Anderson (1917-2012) and Victor Marden (1920- ) formed a partnership under the name of ‘Pearl Shell Products’ in December 1946. By May 1947 Chappell had left, then in 1948 so had Marden.

Government Gazette of NSW, August 1947 page 1929.

Roland Clifford Latter (1919-2000) joined around 1948 and continued the business after Anderson left in October 1950.

Government Gazette of NSW, November 1950 page 3259.

The article below comes from Fisheries Newsletter of March 1950, when Latter and Anderson were working together:

Smith’s Weekly (Sydney), 1st April 1950 page 29.

I can find no further record of the business.

The Newcastle Sun, 10th April 1948 page 3.

The pearl-shell industry, which had stopped during WW2, would not recover this time except for a small market for high end buttons. Broome would reinvent itself around the business of cultured pearls.

Pacific Islands Monthly, 1st September 1958, page 127.

The Bulletin, 16th September 1959, page 19.

World History of Pearl Shell Buttons

You would be forgiven for thinking that the history of pearl-shell buttons begins and ends with the industry in Muscatine, Iowa. Whilst this trade was important, the story is of course, much older and larger than that.

Possibly the oldest shell button found is around 5000 years old from Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley. Some prehistoric examples were carved and pierced so that they could be sewn as ornaments onto clothing.

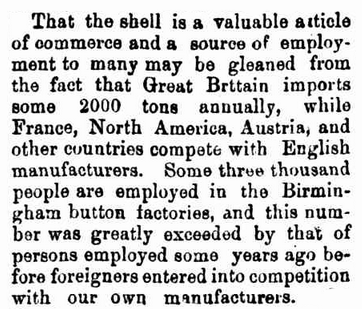

The banning by the United Kingdom parliament of the importation of pearl buttons in the late 18th century lead to a boom in their production in Birmingham, which was already an established button production centre.

The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News, 31st October 1851 page 3. This was before the Australian pearling industry impacted the market.

Above from the book : “Health, Husbandry and Handicraft”, 1861.

Pearl-shell buttons production was labour intensive, with multiple (up to 80 for fancy items!) steps that required manual handling, even after the introduction of machinery into production. The shell used was imported from Australia, the South Pacific, Malaysia and the Americas. A report in 1866 into the Birmingham button trade included a section on pearl-shell. See https://hammond-turner.com/index.php/component/content/article/14-sample-data-articles/125-the-birmingham-button-trade-part-6?Itemid=435

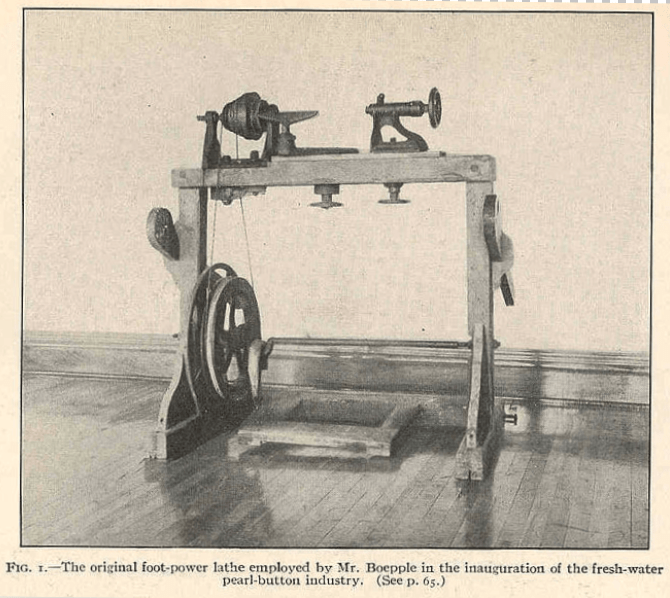

There must have been an industry in Europe as the father of the trade in America, John Frederick Boepple, was an immigrant German button maker with experience in making shell buttons. Due to high importation tariffs , he moved to America in 1887 to avail himself of the plentiful freshwater mussel shells to be harvested from the Mississippi River. Luckily for him, tariffs were introduced in 1890 making pearl shell buttons imported into America expensive. From small beginnings in 1891, a boom industry evolved with a peak of 49 shell button factories and many small backyard units making and supplying blanks. By 1905, Muscatine and neighbouring regions were producing around 37% of the worlds buttons. Muscatine was “the Pearl Button Capital of the World”. Production peaked in 1916, with thousands employed in the industry and millions of dollars earned. However, over harvesting, interruption by WW2, competition from overseas , changing fashions and the rise of plastic contributed to the industry’s decline by the 1950s. Today, plastic buttons are made in Muscatine.

SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FMIB_38301_Original_foot-power_lathe_employed_by_Mr_Boepple_in_the_inauguration_of_the_fresh-water_pearl-button_industry.jpeg

The Australian Woman’s Mirror (magazine), 10th March 1931 page 5.

NB: Small amount of stud buttons were made from American fresh water shell from as early as 1802, according to a report from that year. The fresh water shell that inspired Boepple went in search of 20 years later were probably sent from Illinois in 1872 by William Salter to Germany and reached Boepple’s father, although at the time the potential was not realised.

Shell was exported from Australia from the 1850s until the 1950s to England, America and later, Japan. When Japan was occupied after WW2 from 1945-1952, General Douglas MacArthur was entrusted to revive Japan’s economy. Buttons were among the products made and exported to the world. The words “Occupied Japan” or “Made in Occupied Japan” were required to be printed on products.

Australian shell was also exported to Israel for the production of exquisite, hand-carved, “Bethlehem Pearl Buttons”. The production of shell buttons in Australia occurred intermittently from 1880, but was never significant. See above for more on this topic. According to the British Shell Club, pearl buttons are being produced today in America, China, India, Japan and the Philippines from a variety of species.

http://www.astonbrook-through-astonmanor.co.uk/pearl_buttons.html

http://uipress.lib.uiowa.edu/bdi/DetailsPage.aspx?id=38

https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/pearls/freshwater-pearls/button-capital-of-the-world

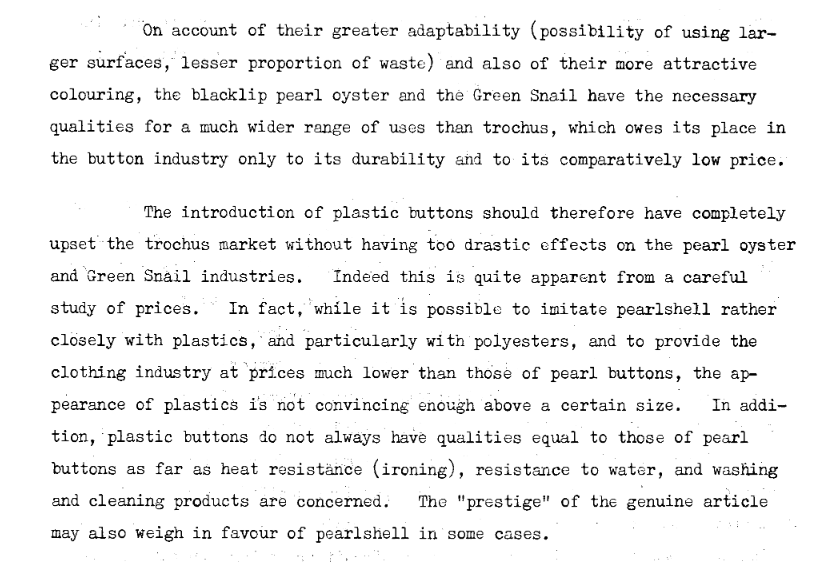

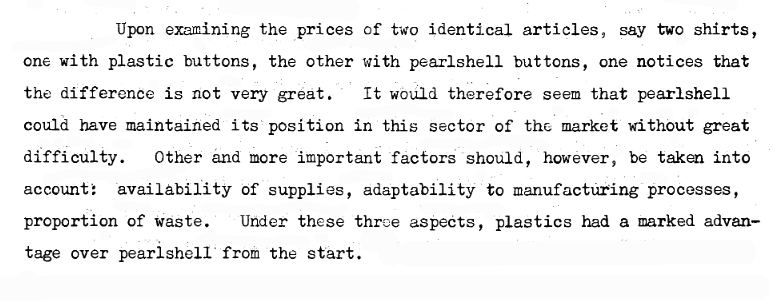

Excerpts from a 1960 article on “The Pearl Shell Market in the South Pacific” detail some of the effects of plastics into the button trade:

A report published in 1997 detailed that trochus harvesting and processing was still an important trade for the Pacific nations. An estimate of an average 1,845 metric tonnes was harvested per year from 1985-1994, which was about 59 percent of global trade. Other countries involved included Indonesia, Philippines, Okinawa and Australia.

The report stated that the first Pacific processing factory was set up in Fiji in the 1950s. Since then 31 factories had been established in 9 Pacific countries, but only 14 were still operational in 1997, employing 213 workers. Only 2 of these produced finished buttons; the rest producing blanks for Korea or Japan.

Japan and Korea were tending to relocate their factories to low-wage countries. There were 20 Italian firms involved in shell buttons, as well as one each in Spain, Germany and the U.K. The American firm Emsig was producing shell buttons in New York, New Jersey and China. There was some production in Mauritius and Madagascar. A button factory in the Seychelles had switched to making jewellery.

The report noted that the shell industry took a major hit in the late 1950 to early 60s, mainly due to competition from polyester buttons, but that there was still a demand for trochus. However, it was noted that growing environmental concerns may further reduce demand for trochus.

For the full report: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/769071468748763703/pdf/multi-page.pdf

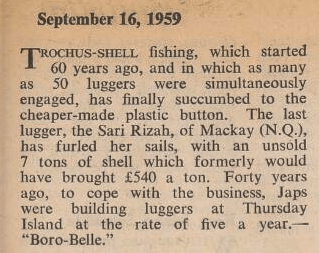

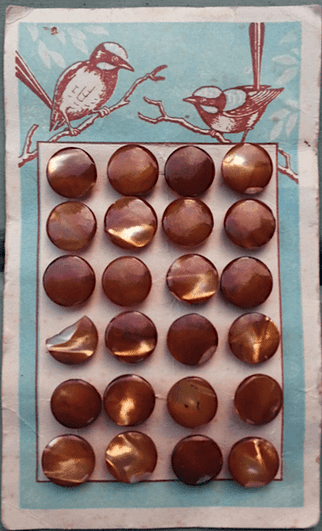

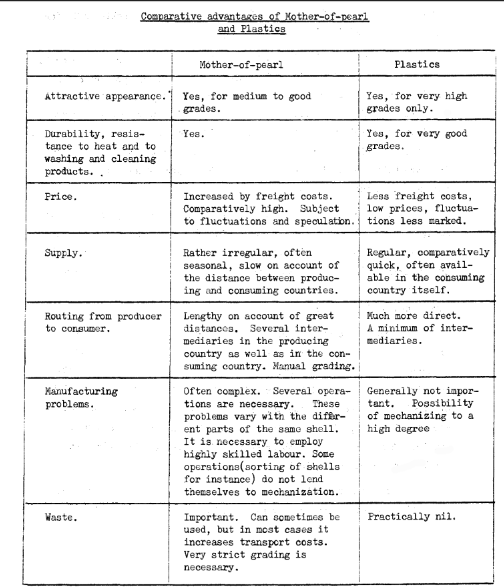

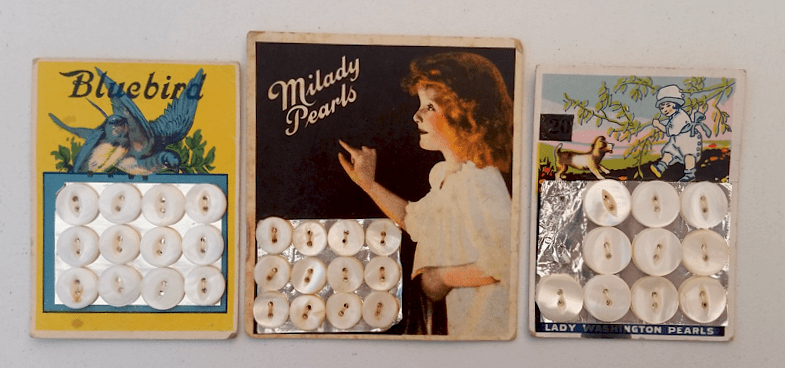

Pearl Buttons Mounted on Foil

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with vintage buttons will be aware that in the past mother of pearl (MOP) buttons were frequently, although not exclusively, sewn onto cards on a layer of silver foil/paper. We often wonder why; was it just to make the buttons look pretty, or was there another reason? When did this practice start? Were other types of backing paper used? For that matter, when were buttons first sewn onto cards?

I assume the sewing of buttons onto cards started with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, when buttons started to be manufactured in large quantities. Certainly outworkers were being paid a pittance to sew buttons and other haberdashery items, such as hook and eyes, onto cards by the 1850s. Charles Dickens wrote an essay, published on 10th April 1852 entitled ‘What there is in a Button’: https://www.onefivenine.info/buttons/Dickens_Household_Words.htm

In part of this essay he addresses the carding of MOP buttons:

The subsidiary concerns of these large manufactories strike us by their importance, when on the spot, though we take no heed to them in our daily life. When the housewife has taken into use the last of a strip of pearl buttons, she probably gives to the children the bit of gay foil on which they were tacked, without ever thinking where it came from, or how it happened to be there. The importation of this foil is a branch of trade with France. We cannot compete with the French in the manufacture of it. When we saw it in bundles—gay with all gaudy hues—we found it was an expensive article, adding notably to the cost of the buttons, though its sole use is to set off their translucent quality, to make them more tempting to the eye.

“The subsidiary concerns of these large manufactories strike us by their importance, when on the spot, though we take no heed to them in our daily life. When the housewife has taken into use the last of a strip of pearl buttons, she probably gives to the children the bit of gay foil on which they were tacked, without ever thinking where it came from, or how it happened to be there. The importation of this foil is a branch of trade with France. We cannot compete with the French in the manufacture of it. When we saw it in bundles—gay with all gaudy hues—we found it was an expensive article, adding notably to the cost of the buttons, though its sole use is to set off their translucent quality, to make them more tempting to the eye.

We saw a woman, in her own home, surrounded by her children, tacking the buttons on their stiff paper, for sale. There was not foil in this case between the stiff paper and the buttons, but a brilliant blue paper, which looked almost as well. This woman sews forty gross in a day. She could formerly, by excessive diligence, sew fifty or sixty gross; but forty is her number now—and a large number it is, considering that each button has to be picked up from the heap before her, ranged in its row, and tacked with two stitches.”

“All gaudy hues”, although expensive, where being used simply to “to set off their translucent quality”. It was (perhaps it still is?) simply a form of marketing!. The use of blue paper makes sense, too. From https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/lost-jobs/in-the-home/laundry/ it is explained that, in the days of washing in a copper (still common in 1950s Australia) that “after the requisite time in the copper, the items were lifted out using a sturdy laundry stick into two or three tubs of cold water for rinsing. In many laundries the last tub contained a bluing agent, to make the wash look whiter”. G. Herring used the same optical effect by selling “boil-tested white” buttons on blue cards.

Here are some examples of cards of fresh-water pearl buttons made and sold in America from the 1890s onwards. These cards probably date from 1910-1950s.

c.1910-1920. Examples using green and silver foil.

Clever use of the colour blue as part of the cards’ artwork, eliminating the need for added foil.