Pearl Buttons on Foil: part 1

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with vintage buttons will be aware that in the past mother of pearl (MOP) buttons were frequently, although not exclusively, sewn onto cards on a layer of silver foil/paper. We often wonder why; was it just to make the buttons look pretty, or was there another reason? When did this practice start? Were other types of backing paper used? For that matter, when were buttons first sewn onto cards?

I assume the sewing of buttons onto cards started with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, when buttons started to be manufactured in large quantities. Certainly outworkers were being paid a pittance to sew buttons and other haberdashery items, such as hook and eyes, onto cards by the 1850s. Charles Dickens wrote an essay, published on 10th April 1852 entitled ‘What there is in a Button’: https://www.onefivenine.info/buttons/Dickens_Household_Words.htm

In part of this essay he addresses the carding of MOP buttons:

The subsidiary concerns of these large manufactories strike us by their importance, when on the spot, though we take no heed to them in our daily life. When the housewife has taken into use the last of a strip of pearl buttons, she probably gives to the children the bit of gay foil on which they were tacked, without ever thinking where it came from, or how it happened to be there. The importation of this foil is a branch of trade with France. We cannot compete with the French in the manufacture of it. When we saw it in bundles—gay with all gaudy hues—we found it was an expensive article, adding notably to the cost of the buttons, though its sole use is to set off their translucent quality, to make them more tempting to the eye.

“The subsidiary concerns of these large manufactories strike us by their importance, when on the spot, though we take no heed to them in our daily life. When the housewife has taken into use the last of a strip of pearl buttons, she probably gives to the children the bit of gay foil on which they were tacked, without ever thinking where it came from, or how it happened to be there. The importation of this foil is a branch of trade with France. We cannot compete with the French in the manufacture of it. When we saw it in bundles—gay with all gaudy hues—we found it was an expensive article, adding notably to the cost of the buttons, though its sole use is to set off their translucent quality, to make them more tempting to the eye.

We saw a woman, in her own home, surrounded by her children, tacking the buttons on their stiff paper, for sale. There was not foil in this case between the stiff paper and the buttons, but a brilliant blue paper, which looked almost as well. This woman sews forty gross in a day. She could formerly, by excessive diligence, sew fifty or sixty gross; but forty is her number now—and a large number it is, considering that each button has to be picked up from the heap before her, ranged in its row, and tacked with two stitches.”

“All gaudy hues”, although expensive, where being used simply to “to set off their translucent quality”. It was (perhaps it still is?) simply a form of marketing! The use of blue paper makes sense, too. From https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/lost-jobs/in-the-home/laundry/ it is explained that, in the days of washing in a copper (still common in 1950s Australia) that “after the requisite time in the copper, the items were lifted out using a sturdy laundry stick into two or three tubs of cold water for rinsing. In many laundries the last tub contained a bluing agent, to make the wash look whiter”. G. Herring used the same optical effect by selling “boil-tested white” buttons on blue cards.

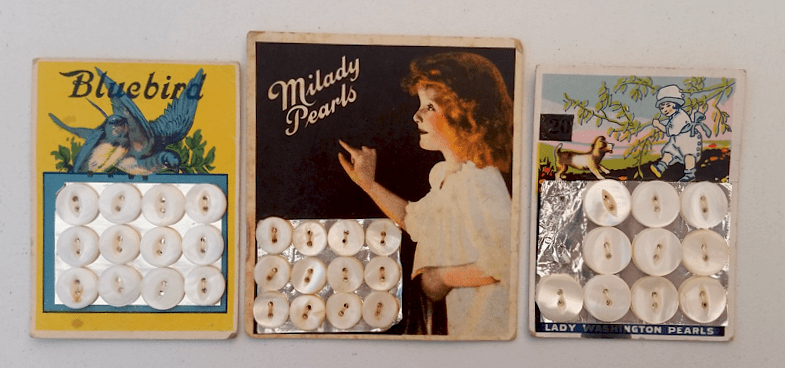

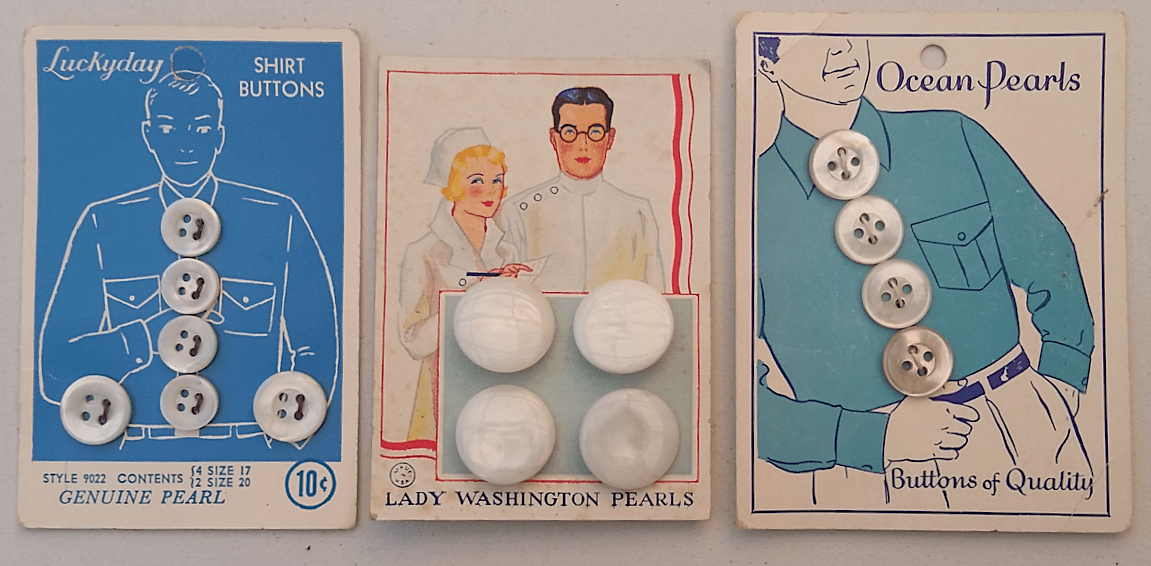

Here are some examples of cards of fresh-water pearl buttons made and sold in America from the 1890s onwards. These cards probably date from 1910-1950s.

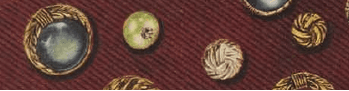

c.1910-1920. Examples using green and silver foil.

Clever use of the colour blue as part of the cards’ artwork, eliminating the need for added foil.

For any comments or questions, please use the Contact page.