AFRICA

Summary of information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

The markets were small. The buttons were re-exported from the mother countries of each colony. Buttons were imported for resident Europeans’ use, mainly pearl, cloth, bone, and metal from Austria, Germany and Italy. In the Kongo pearl buttons were used “on the white duck coats which are worn almost exclusively”. A few brown bone buttons for khaki coats and common bone trouser buttons were also used. There were very few white women in the Kongo, and “the native women generally use pins as fasteners.” The Arab populations did not use buttons on “their native garb.” In Libya the presence of Italian garrisons provided a market for buttons. In Madagascar ordinary white bone buttons were used on all kinds of garments. Most buttons were imported from France duty free.

An article on Eritrea’s industries published in 1946 noted that glass making, including for buttons, was a new industry at that time.

ARGENTINA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There was practically no local button manufacture. Buttons were imported from Germany, France and Italy with pearl buttons coming from Japan. The varieties imported included MOP, ivory nut, horn, papier-maché, metal and bone, especially cheaper grades. A financial depression in the country had reduced trade there considerably since the beginning of 1914.

AUSTRALIA

(As seen by the USA)

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

The population was less than 5 million peoples. All buttons imported, particularly in 1915 from Britain and Japan. Not a large market, but with good credit standing.

Sydney: “is the principal and only commercially important city … a normal English-speaking colonial community, taking its ideals primarily from Great Britain and following British practice in all matters of fashion and dress … The non-occurence of extreme cold weather has its influence upon the demand for buttons suitable for heavy overcoats, etc …but on the other hand the long summers call for relatively large supplies of buttons for light fabrics.”

Melbourne: British buttons were imported duty free, all others had a 10% duty. “Since the beginning of the war the Japanese have entered with a dash, supplying well-made buttons of the cheaper kind, principally pearl.” British celluloid buttons had proved to be of more reliable quality than the American. It was noted that there were summer and winter fashion seasons, and that “..fashions are so precarious that the Australian importers will buy sparingly, say April to July, … and actually be tested in stock on the market. The importers will then cable London for further immediate supplies of such patterns as have proved to be favourites …”

Hobart: Celluloid and metal buttons for women’s dresses made about 65% of all buttons used, “often multi-coloured, though there is no effort made to harmonise the buttons with the pattern of the cloth.” Bone and ivory nuts buttons made up 20% of trade, and pearl about 10%, and most of the remainder were cloth covered. Most of the supply came through Melbourne. Before the war, most were from Germany and since then, England and Japan.

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY

See also below for Czechoslovakia.

This information comes from a magazine published in Prague in 1917, and translated for the national Button Bulletin in the January 1962 edition:

The MOP industry in Austria stated in perhaps the late 18th or early 19th century. The making of these button was at first undertaken by needle makers, because they were in the guild with turners. Later the guild split and the turners would take over this industry, using the same machines they used on wood. The white parts only, in these early days, of the shell were cut out by drilling machines. The shells were polished by hand with pumice and the holes drilled with needles. Later on acid was used to polish large numbers of buttons at a time. By the first half of the 18th century, the industry was centred on Vienna and Prague (then part of the Austrio-Hungararian Empire) although it later decentralised and in some areas took over from the local weaving industry. Workers would often work from 5am til 9pm (and noon on Sundays) although there were no fixed working hours (which probably means wages were low and based on piece-work: Ed) Regulations were introduced in the1880s for 7am to 7 pm working days. Steam engines started to be used in factories from 1888.

Mr Schondorfer of Vienna developed a dye for shell. After a period of experimentation, Austrian button makers were able to make 40 colours, which were mainly exported to America. Unfortunately, the passing of the McKinley tariff caused a massive loss of revenue, although they built up other markets. Many workers emigrated to America. France and Germany started to successfully compete with Austrian products. In the decade before WW1 the price of shell steadily rose. This, along with increased competition (especially from Japan) led to lower wages and a loss of workers, with mostly only cheaper grade buttons produced. Even then, in 1917, the introduction of the early plastics were reducing the production of shell buttons.

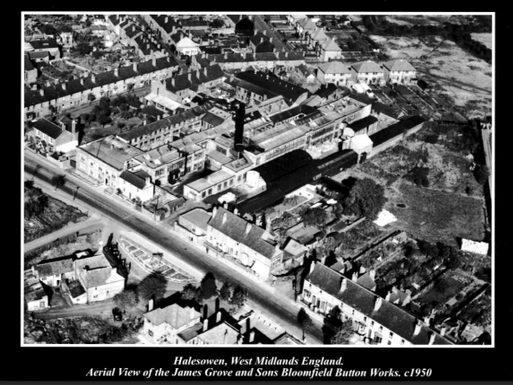

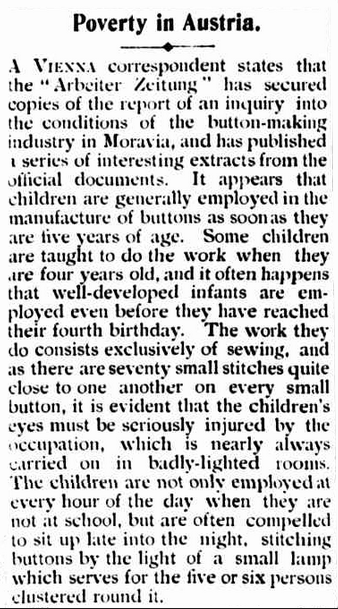

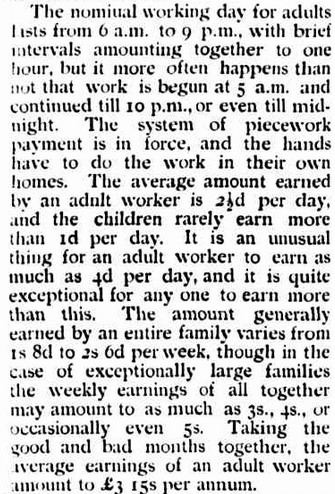

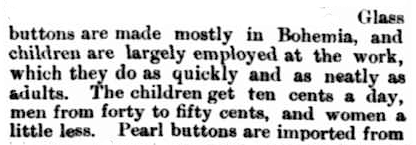

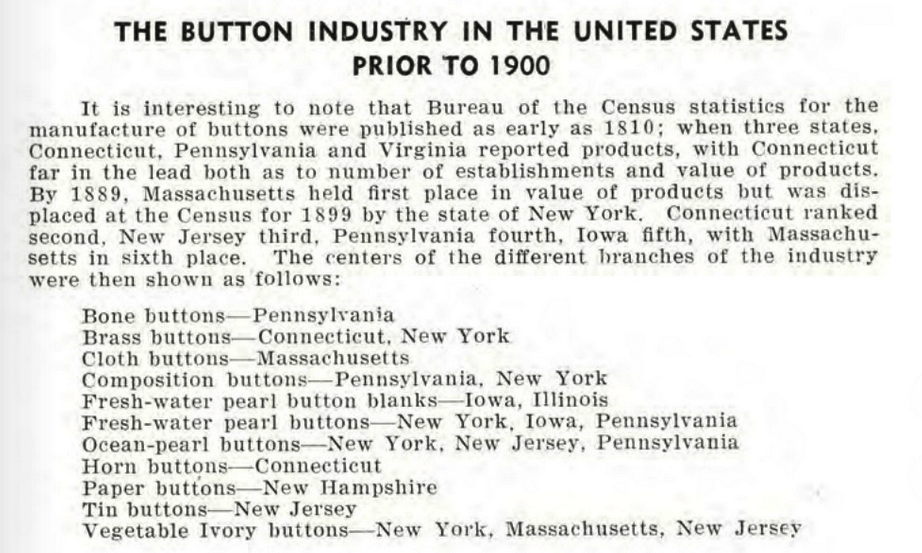

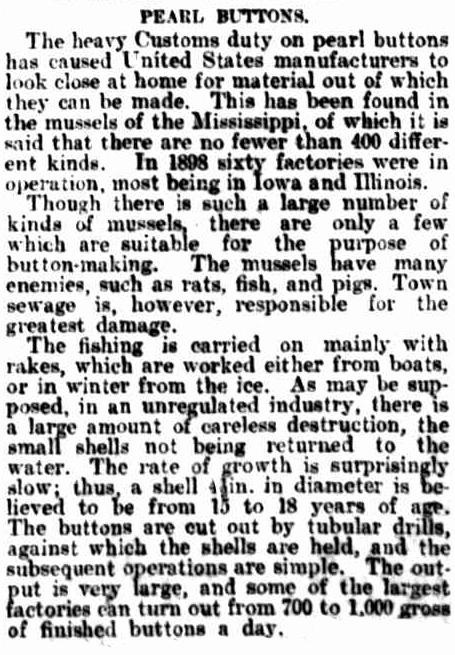

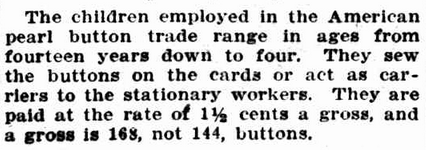

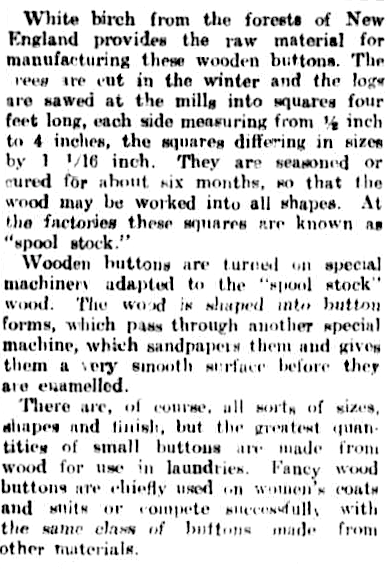

Werriwa Times and Goulburn District News (NSW), 4th September 1901 page 4.

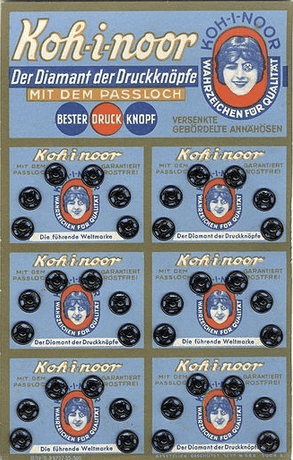

Snap fasteners by the Koh-i-noor factory in Prague, 1902-1939.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

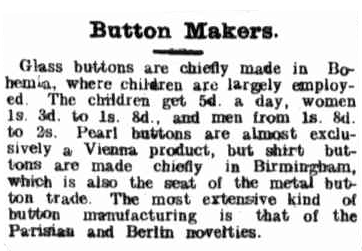

“Northern Bohemia is noted throughout the world as a centre for the manufacture of buttons of almost every type, chiefly vegetable ivory, metal, glass, galalith, silk, linen and cotton covered crochet buttons, and cloth-covered buttons … The principal purchasers are the United States, Germany, England, Russia, Balkan States, the Orient, and South America. Fully 80 percent of the output … is produced by home or house workers.” However, there were 27 factories in Prague that had employed around 5,000 people pre-war making glove, lead, snap, glass, enamel, rubber, buckhorn, wood, horn, bone, leather, linen, paper, MOP, porcelain, celluloid, composition, paper-mache, vegetable ivory, tin, zinc and thread buttons as well as wooden button moulds. Imports were limited to fancy women’s buttons and shoe buttons from Germany and cheap vegetable ivory from Italy.

The MOP industry had been declining even before the war due to increasing competition and reduced supply of shell from the Red Sea.

Toodyay Herald (WA), 29th August 1925 page 3.

BELGIUM

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There were no button factories. Before the war buttons were imported from Germany, France, Austria and England. In 1915 consumers were using existing stock, and not yet able to plan for the future ( due to the occupation).

World (Hobart), 29th October 1919 page 3.

BRAZIL

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

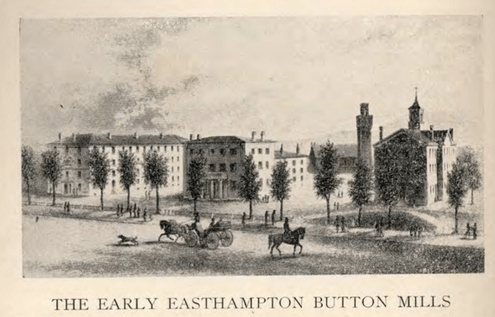

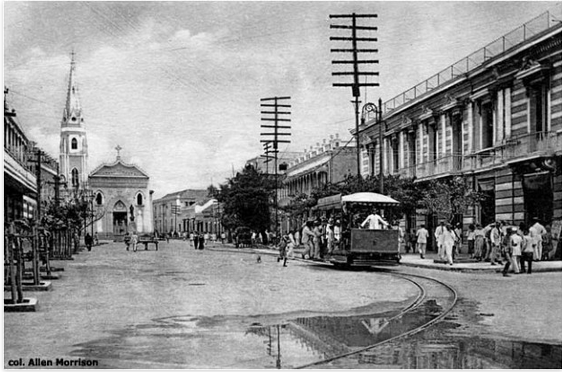

There was a small industry unable to supply local demand. Only one factory was manufacturing pearl (from imported Japanese Takase) and metal buttons in Rio de Janero. The metal buttons were for uniforms mainly made from copper sheeting imported from France. However, with the war time ban on copper exporting, local foundries were making copper sheet from scrap. A limited amount of higher quality buttons for officers’ uniforms were imported. There were small local concerns making covered, composition, and bone buttons.

Large amounts of buttons (especially cheaper varieties) were imported, mainly from Germany and Austria-Hungary (before the war), and from Italy, France and Portugal, including wood, glass, bone, horn, composition, MOP, ivory and celluloid. It was cheaper to import completed vegetable ivory buttons from France and Italy (and Germany pre-war) than make them from local supplies!

It was noted that American buttons cost twice as such on average as European buttons to import.

BRITISH GUIANA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

In 1915 buttons were chiefly being imported from USA and England; mostly cheaper varieties of pearl, glass, bone and metal. It was a small colony, with many of the East Indian and native population using few buttons.

BULGARIA

Eurobuttons

This company has its factory in Bulgaria, producing buttons and other products. They produce polyester, urea, coconut, “corosso”, MOP, wooden, bone, horn, metal, and fabric covered buttons. They make brass and “lock” metal buttons (by which I think they mean tack buttons for jeans). They are located in Mogili.

Meo Buttons

Located in the city of Rousse, it is the largest button factory in Bulgaria, making agoya shell, horn, corozo, and polyester buttons.

CANADA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

The industry was not large, with 15 factories in 1915. The main factories were located in Berlin (now called Kitchener) Waterloo, Toronto, Ganonoque and Montreal. America supplied 53% of its imports in 1914, rising to 64% in 1915. In Montreal the buttons made were mainly hand crochet, mohair and celluloid, and predominantly produced by makers of braid, cord and tassels rather than dedicated button producers. In Ottowa they made bone, metal and composition buttons. Wood buttons were also made in Canadian factories. In Ontorio manufacturers made vegetable ivory and fresh-water pearl buttons. Agate buttons were sourced from England and France, as they could not be sourced from America. Salt-water pearl buttons were being imported from Japan. There was an opportunity for American makers to meet the supply of fancy pearl and celluloid buttons previously sourced from Germany and France.

Queensland Times (Ipswich), 13th August 1940 page 3.

In the early 20th century Berlin was referred to as ‘Buttonville’ due to the many button factories there, mainly producing vegetable ivory and pearlshell buttons but also horn and wood. Most Canadian button factories had closed by the 1960s due to foreign competition as well as the use of new materials.

Canada Buttons Limited

This started in 1884 in Montreal as Dominion Button Works, changing to Canada Button Limited in 1918. It has been known as Boutons du Canada Ltee since 1987. It was a pioneer in making plastic buttons in Canada.

Dated 1967.

Dominion Button Manufacturers Ltd.

This firm started in 1870 making vegetable ivory buttons as the Pioneer Button Works in Berlin, Ontario, the first button factory in Canada. It was renamed the Shanzt Button Manufacturing Co in 1871, the Dominion Button Works in 1872, the Jacob Y. Shantz & son Co Ld from 1891-1912, then the Dominion Buttons Manufacturers Ltd. from 1912-1964. Around 1875 the production of pearl buttons was started, both MOP and fresh water types. In the twentieth century the factory started to make casein, bakelite then plastic buttons. The factory closed in 1964.

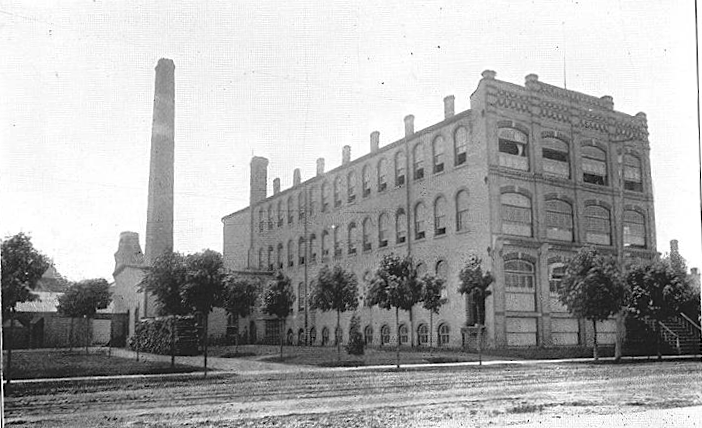

Dated 1906.

CANARY ISLANDS

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

The stocks of buttons previously bought from Austria and Germany had run out. Bone, pearl and pressed metal buttons for overalls were the main requirements.

CENTRAL AMERICAS

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Overall the market was moderate to low, due to many people being too poor to wear clothes requiring buttons. In some areas, only buttons that could to stand up to the hot humid conditions were suitable. “Horn deteriorates, composition splits, and metal buttons rust out.” A lot of white, washable clothes were worn. The only buttons made locally were cloth covered over wooden moulds. Most buttons were imported from England, Austria, Italy, Germany and France. Shipping and low pricing were issues to be resolved by potential American exporters.

In British Honduras the preferred buttons were vegetable ivory buttons for coats and vests, coloured to match the fabric, with cheaper versions for trousers, plus a smaller quantity of brass buttons for men, plus pearl and linen buttons for women. In Costa Rica the market required pearl, bone, vegetable ivory, metal and cloth covered buttons. In Gutemala some glass and porcelain buttons were imported, also cloth covered and bone buttons. French style, rather than American were preferred by upper class Gutemalians. In Honduras pearl, white china, bone vegetable ivory and non-rusting metal buttons were used, but the demand was not high. Puerto Cortes required pants buttons in bone, composition or metal, white china and pearl. There was low demand from Nicaragua, but some bone, horn, composition, china, vegetable ivory, celluloid and glass buttons were imported. Panama mainly imported white and light coloured buttons to match their light coloured clothing; mostly corozo, metal, glass and cloth covered. In Salvatore the most favoured buttons were glass, metal, and corozo.

CHILE

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Manufacturing consisted of one establishment in Santiago making around 20 gross per day, mostly shoe buttons, and the lack of experienced workers was limiting the ability to increase production. Therefore most buttons were imported from Germany, Italy, France and Great Britain and the USA; horn, bone, leather, MOP, vegetable ivory, wood, metal, shoe, rubber, covered, and paper. Black mourning buttons were important due to the custom for deep mourning. They had in the past imported nearly all their military buttons and supplies from Germany, so by 1915 the supply was nearly gone.

FROM THE ETHNIC JEWELLS MAGAZIE: Mapache (South-central Chile and south-western Argentina) women.

It was noted that the custom of wearing black shawls that covered the head and 3/4 of the body by Chilean women of the lower and middle classes, as well as for all classes outside major cities, reduced the demand for fancy blouse buttons and for buttons used in tailor made clothing. Therefore most buttons used were cheaper varieties and reused for generations. Those wealthy enough to follow fashion bought from Paris or London, not America. However, since the outbreak of war European manufacturers, particularly of metal buttons and snap fasteners, had not been able to provide supplies, so there was an opening for American exporters.

CHINA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

“The ‘button’ in general use by the Chinese in their native style garments is the ingenious cloth knot of the same material as the garment; the buttonhole is a small loop of the same material stitched in braid form on the garment.”

‘Frog fastening’: Western use of Chinese style fastening as depicted in The Australian Women’s Weekly. 14th March 1936 page 8.

“For many years brass buttons, globe or ball shaped, with ground surfaces worked up in a variety of fancy decorations oftentimes bearing a stamped design of some Chinese conventional character, signifying happiness, long life, or wealth, constituted the bulk of the imports of foreign buttons. Since the 1911 revolution in China, however, the use of these globe or ball-shaped buttons has fallen off. In their place are found fancy buttons in various styles, usually on the garments of the women, the ornamental parts being of vari-coloured glass, principally to appear like diamonds, set in brass or other metal.”

“As to foreign staple buttons, these are, of course in used for … the foreign resident … and by Chinese who have adopted the foreign style of dress.”

Excepting for some cheap buttons, including pearl and brass, manufactured around Canton, there was no button manufacturing in China. The shell and bone buttons were all hand made. Imported snap fasteners were imported from Germany pre-war, since then from Japan. Fancy buttons were sold in sets of 5 mounted on cards, as that was the number usually found on the front of a Chinese gown.

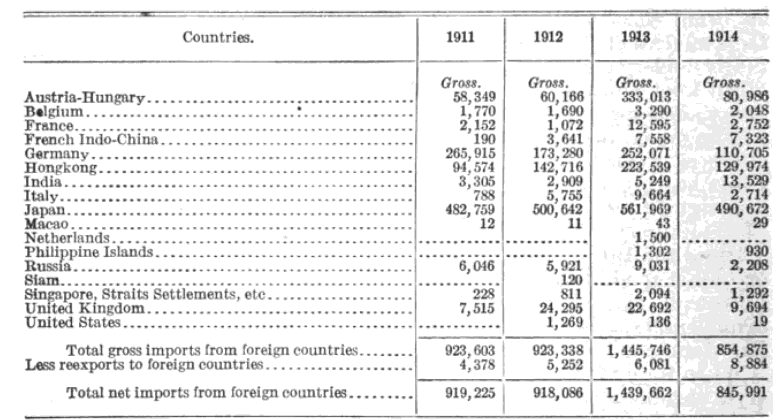

“Buttons, brass and fancy” imported into China. Note that Hong Kong was only a trans-shipment point for foreign supplies. The Japanese buttons were mostly very cheap ones.

Hong Kong (and Southern China):

Nickle covered steel was not suitable as it rusted in the climate; bronze-nickle was better. Bone buttons could become oxidised. Some glass and Japanese pearl and cloth-covered linen buttons. Irish crochet buttons made in local convents were sold by hawkers.

Northern China:

As for Southern China, cheap brass, pearl, imitation pearl and bone buttons were chiefly used. It was noted that the Japanese in this area tended to own at least one foreign-style suit for business and dress clothes, as well as wearing foreign-style overcoats. Buttons here were all imported, chiefly from Japan but also Austrian, including metal, bone, porcelain, shell, buffalo horn, and nuts. No buttons were manufactured here.

COLOMBIA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Colombia had no local manufacturers, but supplied large quantities of tagua nut to the world. The use of buttons was limited “by climatic conditions, and many persons (being) scantily clad.” The general use of white clothing limited choice of buttons used to mostly white, including those made of porcelain, bone and pearl, from France, Germany, USA and Britain.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

The nation of Czechoslovakia came into being in 1918 after the break-up of the Austrio-Hungarian Empire. This lasted until 1993 when it split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The area of Northern Bohemia, including Gablonz (later Jablonec), had specialised in glass making from the 16th century due to the availability of sand, water and trees (for fuel) need in glass production. Glass making in Bohemia started as far back as the 13th century. Glass inserts for buttons started to be made by the 1760s (apparently the first glass mould for making glass buttons was invented in 1732) , followed by the development of glass buttons with metal shanks. Black glass buttons, all the fashion in Victorian times, came from this region.

Part of a larger article in the Hamilton Spectator (Victoria), 20th July 1882, page 3.

The Telegraph (Brisbane), 19th October 1904 page 7.

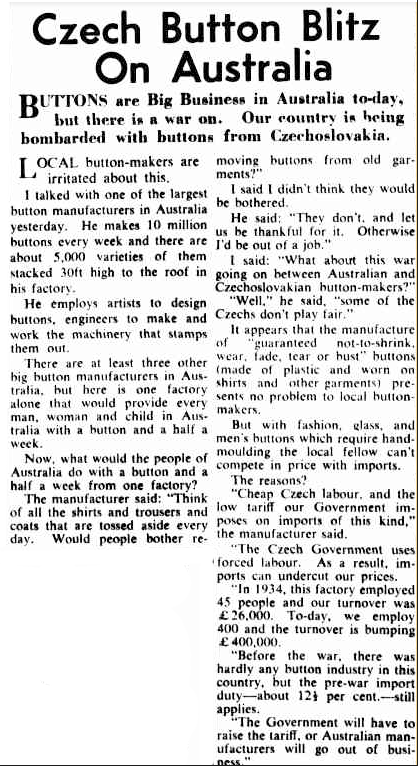

The Northern Herald (Cairns), 27th February 1937 page 44. The situation would soon change …

The Sydney Morning Herald, 10th May 1939 page 12. From an article discussing the effect of the embargo on Germany’s trade during the war.

Glass production continued after the break up of the Austrio-Hungarian Empire after WW1. The area was occupied by the Nazis from October 1938 until May 1945. During that time, some Czech craftsman who had fled to Britain and other countries used their skills making buttons and other items for the war effort.

Post 1945 most ethnic Germans were expelled, often at short notice, despite having lived in the region for generations. Some of these settled in Germany, and would restart a glass button industry there. The area that many moved to became known as Neu Gablonz.

The Age (Melbourne), 31st May 1949 page 6.

South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW), 18th September 1950 page 1 feature section. This snippet appeared in newspapers around the country, and says much about our paranoia about communism at the time.

The Sunday Herald, 8th October 1950 page 2.

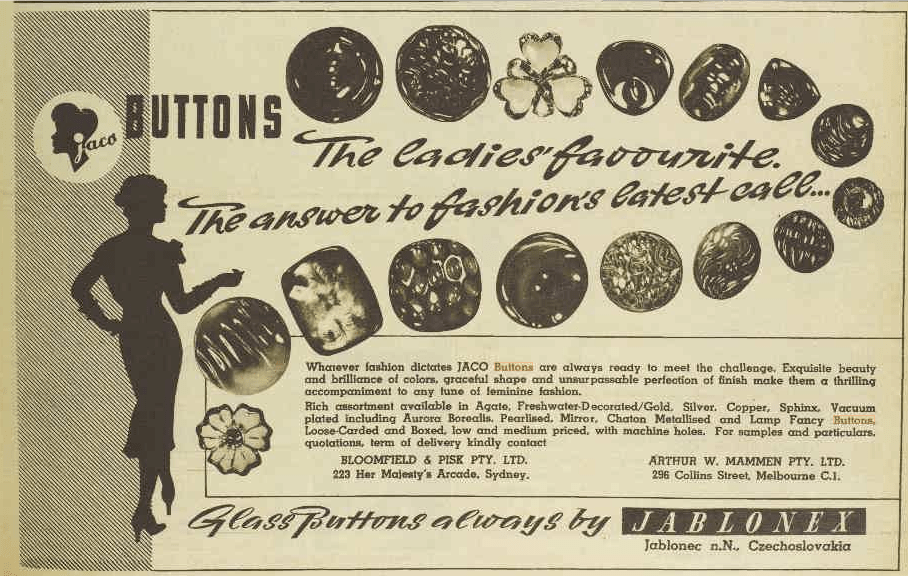

From post WW2 until 1981, under Soviet control, much of local production, of lower quality, was for communist bloc consumption only. Only only state owned company, Jablonex, was allowed to export from the region at this time.

Australian Women’s Weekly, 9th April 1958 p 53.

International trade resurged with the lowering of the iron curtain in 1989. Jablonex no longer had a monopoly on the trade, although it tried to regain control of the industry by buying up other companies. In 2008 the company folded. They had not been able adapt and survive in the freer market. Much of its former business is now owned by Preciosa.

https://www.hglass.cz/history-of-glass-buttons/

https://kraftika.shop/en/czech-glass-handmade-buttons-history-size-and-color-charts/

http://www.wildthingsbeads.com/article-tcgb-wmi.html

DENMARK

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Apart from a small amount of hand-made buttons, there were no local manufacturers. Most imports came from Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Japan.

Popular buttons in 1915 included ‘soft-back’, silk covered and ‘three-fold’ linen, horn, celluloid, pearl, vegetable ivory, glass and composition. Metal buttons very less popular but still used for uniforms, trousers and fancy. Vulcanite buttons were imported from America.

ECUADOR

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There was no local manufacture. The button trade limited mostly to cheaper types; small amount of MOP, vegetable ivory, bone and metal from Germany, France, Britain, and since the war, mainly from the USA and Japan.

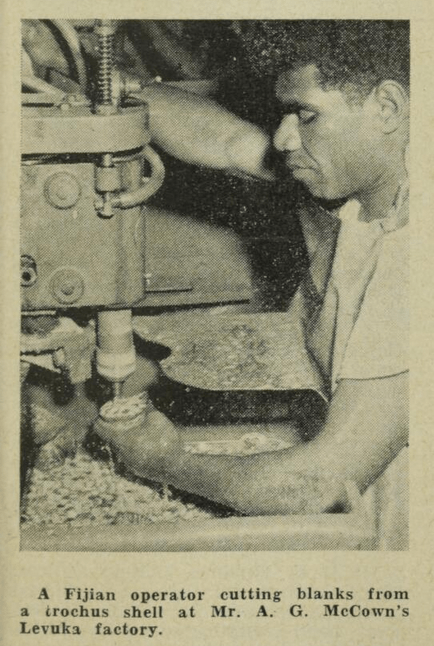

FIJI

In the 1950s turtle shell button inlaid with silver were sold for the tourist trade. In 1953 and 1954 two companies set up shell button factories in Fiji under government protection. Despite this, the local industry was dead by 1959 due to competition from Japanese manufacturers and from synthetic buttons.

Pacific Islands Monthly magazine, May 1953 page 50.

Pacific Islands Monthly magazine, 1st November 1954 page 145.

Pacific Islands Monthly magazine, 1st November 1954 page 145.

In a November 1991 magazine there was a brief mention of a small button factory closing down due to difficulty in purchasing trochus at affordable prices. Apparently the Korean and Japanese pay higher prices than Fiji can afford to.

FRANCE

In the middle of the 12th century trade guilds were set up, including for ’boutonniers’, and ‘paternotriers’ that is button makers working in metal or horn, bone and ivory.The first hand carved mother-of-pearl buttons may have originated in France in the 17th century.

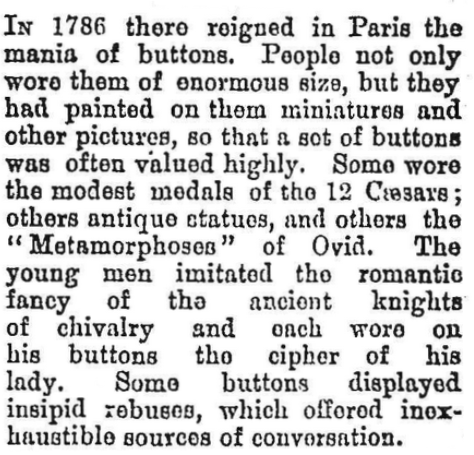

Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 11th September 1897 page 9. This is a small excerpt from The Pocket Magazine, or Elegant Repository, for the Year 1794, about fashion in France pre-revolution.

The industrial revolution (approx. 1760-1840) was starting in Britain at the time Diderot’s prints were made. However, industrialisation in France would lag behind that in Britain by decades. In part, this was because of the French Revolution and its aftermath (1789-1871) which saw a cessation of trade with Britain and so a delay in the newly developed machinery being able to be imported. Entrepreneurs moved abroad or were executed. Also important was the relatively low population growth of France (40%) versus Britain (350%) and a great deal of poverty, both which reduced consumer demand for new products, and a greater proportion of peasants tied to the land rather than seeking employment in factories. Another factor was the lack of supplies of coal and iron to support new industries.

When industrialisation did occur, as for Britain, it started in textile manufacturing. With industrialisation there developed a new working class. As late as 1906 most factories were small in size with less than fifty people. Skilled artisanship suffered, as it did elsewhere, by competition with factories, however, small industry was to a degree more protected and preserved by the the special value placed on the manufacture of luxury goods by the French. Historically this had been given great support by the court of King Louis XIV with its high consumption of luxurious and fashionable clothing and other goods. As well as the royal patronage, there had been high import tariffs which protected local artisans, but may have stifled innovation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_fashion

Quoting from Primrose Peacock’s book, Discovering Old Buttons, ” During (the nineteenth century) European manufacturers, especially in France, lost much of their eighteenth-century pre-eminence and were in some cases slow to mechanise. Good quality buttons were, however, constantly produced by an industry largely based in Paris, with ‘Trelon, Weldon and Weil ‘and ‘Albert Parent & Co.’ being the leading manufacturers.” By the late 19th century, France had caught up with the advantages Britain had gained via the industrial revolution.

According to John P. Turner in 1866, there were 80-100 makers of metal buttons, 70-80 for covered buttons, and 70-80 for other kinds.

Méru

The town of Meru, north of Paris, was the centre of MOP and shell button production from the end of the 19th century until 1972 (or until after WW2, depending on the source).

https://parisdiarybylaure.com/a-museum-for-mother-of-pearl-is-a-true-find-an-hour-north-of-paris/

A violent strike of button workers took place in 1909.

The Telegraph (Brisbane), 5th June 1909 page 17.

‘Reports of artisans / selected by a committee appointed by the council of the society of arts to visit the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867.’

This report included a sections titled “On Buttons” by S.W. Richards, a manager of Button Works, Thomas Johnson, Tool-maker and also by William Bridges, Button-tool Maker, all of Birmingham. Summarising from these reports:

The button trade was growing in Europe. In France alone 22,000 people (8,000 men, 10,000 women and 4,000 children) were employed in the trade. An estimated 2,500,000 kilograms of metal was being used annually and a similar quantity of silk and other fabrics. Two thirds of the output in Paris and district, valued at approximately 4,000,000 francs, were for export. Some disadvantages for the English button manufacturers were noted compared with the French. Firstly, although English manufacturers could still make good quality gilt and plated buttons, the fashion in England had changed from these towards covered buttons with a resultant drop in the metal button trade there whilst it was still strong on the Continent. Also, there were high import tariffs in Europe. Lastly, the English could not compete with the Parisians in terms of reputation for luxury articles. As a result, English manufacturers had not been able to take advantage of the growing worldwide market for mantles, robes, and dress ornaments despite being able to produce the same, if not superior, quality specimens. It was noted that the button trade had grown large in Germany as well.

“The style of the French makers is superior, and as in some of the German cases (of buttons), we have a triple combination in some of the patterns – namely, an outer rim of metal, either gilt, oxidised, or bronzed, with a japanned centre inlayed with pearl … the die-sinking of the patterns where the rims are ornamented is good, truthful effective, and well designed.” The quality of coloured glass was noted to be far superior to anything produced by English glass makers. The author was concerned that a lack of good quality art schools in places like Birmingham was putting the trade in England at a disadvantage compared with the skilled workforce available on the Continent.

Some of the exhibitors, now lost in the mist of time, at the 1867 Paris Universal Exhibition included:

A. Masse & Co. – Quality livery and uniform buttons in gold, silver, gilt and enamel. Sporting buttons in oxidised silver and high-relief designs. Flat and ball coat buttons in black terry velvet.

Caillebotte & Co. – Horn buttons, including colours within indented rings.

Duchel et Fils, Paris – Horn buttons moulded using high quality dies.

F. A. Bagriot, Paris – Fifty line sized button of onyx cameos mounted in coloured gold. Quality livery and uniform buttons in gold, silver, gilt and enamel.

Gourdin & Co – Quality livery and uniform buttons in gold, silver, gilt and enamel. Also vegetable ivory.

Hartog, Jean & Co., – Linen buttons including “balls, spires and convex with flexible backs, and covered with diamond cloth, of a very superior quality.” Also silk, velvet, fancy dress, sporting,livery and uniform buttons, “upwards of 5,000 different patterns” Three -quarters of their display of covered buttons were convex silk ladies’ dress buttons. There were also silk balls, flat silk, fancy shapes, and those with “metal drops attached by short chains”.

Mr Hartog and Jean were late of Trelon, Weldon & Weil.

J. B. Huet, Paris – Steel buttons flat and shaped as balls, spires and half balls in small sizes.

J. F. Bapterosses – “an excellent and good assortment of porcelain buttons”. See more on this company below.

Jules Plançon, Paris – buttons with imitation gems mounted in pearl. Designs included carved heads of animals, classical heads, etc. “Paper buttons in ever imaginable shape. many inlaid with metal, glass, pearl and coloured japanned centres, of various shapes.” Bronze rimmed buttons.

Lebeuf- Milliet & Co., Montereau -ceramic buttons from 10-100 lines in size. Cheap China shirt buttons. The author noted that there were no English manufactures of these buttons, although Minton & Co as well as Chamberlains’ formerly did.

Lemesle, Paris – brace buttons, gilt and japanned. Fancy gilt-plated and oxidised metal balls. Small-shanked paper buttons japanned and various colours. Pinched solid glass buttons.

Maillot & Vincent Hardy, Paris – Steel buttons in oval, spire top, oblong, barrel and ball shapes as well four-hole.

Marie & Dumont, Paris – MOP buttons. shirt buttons from 10 lines upwards, in two-hole, four hole,convex,concave, fish eyes, etc. The author noted that a design having “a fancy bevel edge with a small ball in the cup, and four holes around the ball was a favourite pattern with the French.” Vest buttons in 18 and 22 lines. 16 line “balls” of unusual design … “Imagine as one shape, a ball with deeply cut circles rising from the base to the apex, leaving only a core in the centre.” Mantle buttons and ornaments “for which the French are famous … in turned and carved work, cameos, precious stones and pieces of different coloured pearl shell being inlaid… a set of mantle buttons of some of the designs would cost more than the mantle …”

Masse & Co., Paris – Horn buttons of good variety and design, including classical heads. Fancy gilt, plated and oxidised buttons. Enamel.

Neau & Lecomte, Paris – Florentine buttons, enamel gilt, four-hole suspender with lettering either raised or sunk upon the surface. Pierced top dress buttons. Lithograph button that had “a poor look”.

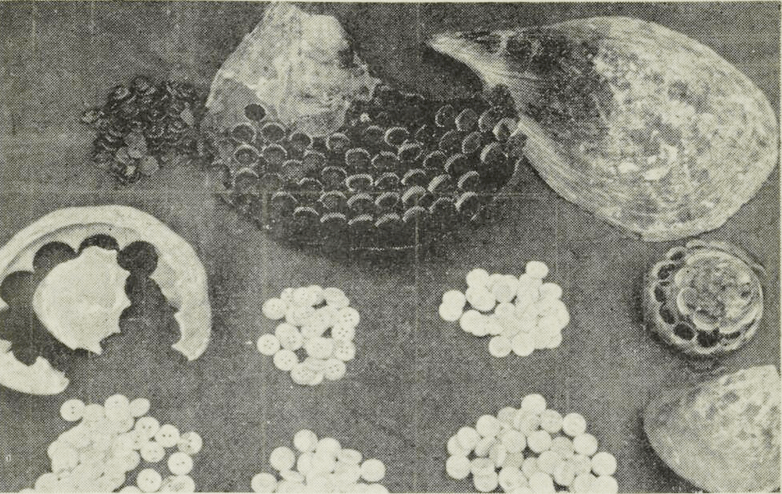

Parent & Hamet, Paris – fancy dress buttons including plain silk, satin, velvet, terry silk, linen, needlework, pearl, metal, and glass with mosaic centres. Also Florentine, silk balls in gilt bands, silk covered oblongs, crystal set in claws (the writer noted that the English were unable to compete with the continental makers in this class on price or quality). See more on this company below.

Roulinat-Lemesle et Frére, Paris – Fancy dress buttons including mother-of-pearl in combination with gilt rims and good quality glass centres. Also Florentine (fabric covered), coloured silk and ‘gilt shell four holes with bronzed centres”.

Manufacturers

Albert Parent & Co.

This information came mostly from the National Button Bulletin of July 1985:

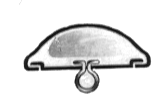

In 1825-1850 a button company was formed by Victor Le Tourneau, Alfred Patent, and Th. Hamlet. The backmark used was L P & H. From 1840 they used the trade mark of a beehive. In 1844 Parent developed a new type of button shank.

During 1858-1868, the firm continued under the leadership of Albert Parent and Th. Hamet (a cousin of Parent). From 1868-1888, the company was headed by Anatole Parent (son of Alfred) and Hamlet. The backmark accepted for these periods was AP & H or PH.

From a 1867 trade show report reproduced in the September 1947 issue of the National Button Bulletin, page 272.

In 1883 four trademarks were registered for AP & H in USA (Beehive, Beehive plus woman, bull) The buttons had cone backs.

During 1888-1894, the organisation was known as Anatole Parent & Company. A Mr Bouchard joined the firm during this period, and the backmark was P & B & Co.

From 1894-1912, the name was Albert Parent & Company (son of Anatole, grandson of the original Albert). He married Bouchard’s sister. The trade mark was A P & Cie

The firm continued until 1977 but not many buttons were made:

1912-1916: worked with Lieger

1912-1923: worked alone

1923-24: Albert Parent

1924-41: Albert Parent & Co (1939-1946 closed during war)

1941-61: Parent

1962-77: Parent & Corona

1978-1998 or later: ETS Parent et Corona

Robert Parent, (son of Albert, 4th generation of Parents) joined in 1924 as did a son-in-law Georges LeBarazer.

Over the years the company produced many types of buttons, including:

1825: metal, silk buttons

1865: enamel, silk, steel, pearl

1866: enamels, pearl, paper mache, silk

1867: crystal, horn

c.1875 enamel, papier-maché, horn

1876; ‘base of horn’

1878: horn molded with pearl

1881: metal ‘with engravings and stampings’

1883 ‘horn with caps of copper’, engraved vegetable ivory

1890: pants buttons with ‘stamped metal caps and bars’

J. F. Bapterosses

From Wikipedia: Jean-Felix Bapterosses 1813-1885.

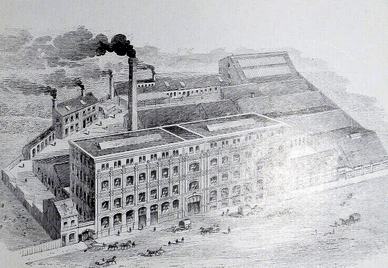

The ‘Bapterosses & Cie’ factory, founded in 1845 in Briare, France was so successful in the making of ceramic buttons, that they dominated in the field. In 1866 there were around 700 people working there. From the 1866 ‘The Working Man’ weekly newspaper: “The moistened clay is pressed into moulds, formed of plaster of paris, after which it is carefully placed on boards to dry, and subsequently taken to the biscuit-oven where it receives the first firing, or “baking”. The baked clay is now called biscuit, and is ready for the painter or printer. Many of the porcelain buttons are uncoloured, but a greater number, both with holes and shanks, are painted, either wholly or in part; some receive complicated designs, others are simply ornamented with coloured rings. The painting is either done by hand or by means of transfer printing; but in either case the colours are “fixed” by the articles being baked in a muffle-furness or an enamel-kiln.” The buttons could then be glazed if required, and shanks added.

A firm which merged with that of Baperosses in 1851, Emaux de Briare, is still in operation, specialising in mosacics.

Nacryl s. a.

This is/was a plastics moulding company in La Trinité-près-Nice. Sales cards of plastic/diamente buttons are seen for sale online.

Trelon, Weldon & Weil

In 1835 Nicolas Trelon and Louis Langlois-Sauer founded ‘Trelon and Langloi-Sauer. They were joined by Weldon in 1841. On the 1st January, 1845 by Henry-Marsch Weldon, Nicolas Trelon and Louis Weil and formed the partnership of TW&W. They specialised in military buttons, but also other uniform buttons such as government, hunting and fashion. They supplied buttons to troops on both sides of the American Civil War. In 1865 TW&W became Trelon-Weldon-Weil Hartog and Marchand (TW&W HM).

The company was renamed Coinderoux in 1904 but went into liquidation in 2007. Janier Gruson Prat bought the company and is still manufacturing metal buttons.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

French women working in a button factory at Briare, September 1917. (From blogberth.com)

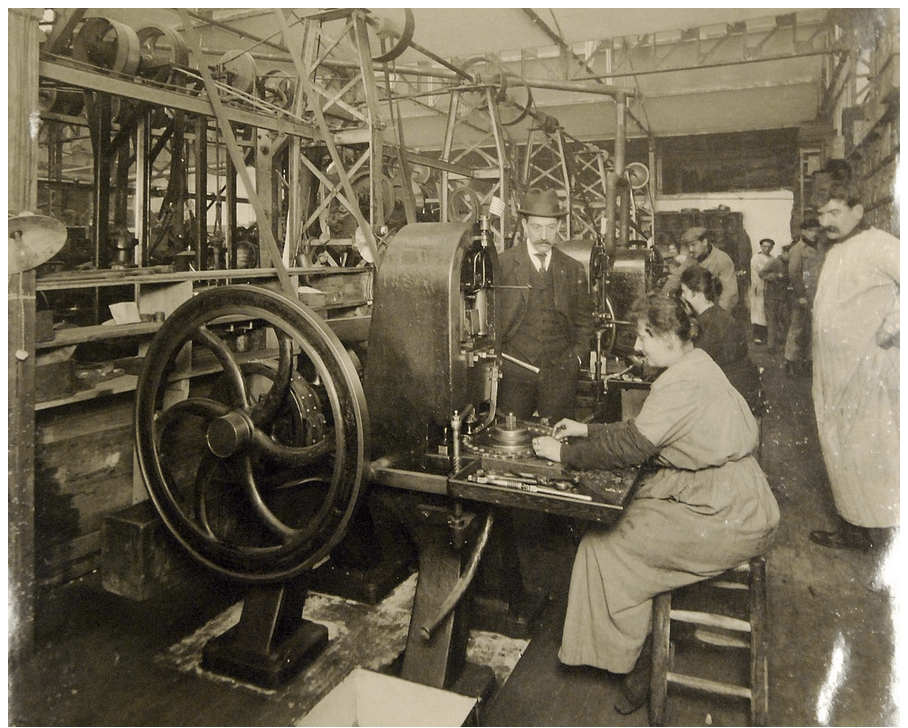

Lot-8319-4: A button stamping machine at Henri Jamorski Button Factory, Paris, France, January 3, 1919. U.S. Army Signal Corps Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. (2016/07/22).

The ‘Syndicate of French Button Manufacturers’ estimated that the normal (non-wartime) production of buttons totaled US$5,790,000 to 6,755,000 in value. Materials used included pearl, bone, horn, polished and enameled and coloured metals, porcelain, glass, jet, vegetable ivory, ivory, tortoise shell, celluloid, wood, silk, mohair, linen, other textiles, leather, precious metals and stones. Different centres in France specialised in varying types of buttons; Paris for fancy/fashionable products; Oise for corozo, bone and pearl; Loiret for porcelain; Haute Garonne for bone; Charente, Vosges, Main-et-Loire and Isere for pearl. Isere also produced snap fasteners.

Despite the large production for home use and export, some buttons had still been imported from pre-war Germany, Austria-Hungry, England, Italy (corozo) and Japan (pearl). Since the war more buttons were coming from Italy and England. There were shortages of metal snap fasteners, hat-pin tops and cuff buttons. According to a 1946 trade magazine, MOP buttons were not made after 1941 due the inability of sourcing supplies. Likewise for corozo nuts, with manufacturers using wood as a substitute. The button industry was still centred in Paris. The manufacture of metal buttons was still limited. Plastics and bone were hard to source. However, things were improving.

FRENCH INDOCHINA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

This included the regions of included Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Guangzhouwan. No buttons were manufactured there, with around 20,000 kilos imported annually. There use was mainly limited to Europeans and the Chinese business community.

GERMANY

Iron jewellery, including buttons were made in Berlin in the first half of the 19th century.

In 1887 the “British Merchandise Marks Act” required that all products to be sold in Britain were marked with their country of origin. This was to discourage the British from buying foreign, particularily German, products in favour of their own. It was not necessarily a successful campaign, as some countries developed a reputation for quality (i.e. Garmany), so that the products became more, rather than less, desirable.

Examiner (Launceston), 31st March 1900 page 11.

In 1905 a new company, Galalith Gesellschaf Hoff & Company, bought out its French galalith manufacturing rival, creating a European monopoly of Galalith production. Galalith was to become a popular plastic for the production of buttons.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

“The button industry of Germany, which is probably the largest in the world, is centred principally in Saxony and the Rhine Province. Many millions of metal buttons are manufactured for military use, and there is scarcely any other hard substance, organic or inorganic, which is not utilised in Germany for the manufacture of buttons. Button making materials, especially the ivory or corozo nut, are imported in immense quantities at Hamburg, beyond even the needs of the German button manufacturers, Hamburg is, in fact, the largest market for button-making materials in the world … Only ivory-nut, glass and pearl buttons had been imported into Germany to any extent.” Vegetable -ivory button were imported for men’s clothing as it had been cheaper to import from Italy, although they did also make their own, mainly in Schmolln. Fancy glass buttons had been imported from Bohemia.

Hamburg c.1912

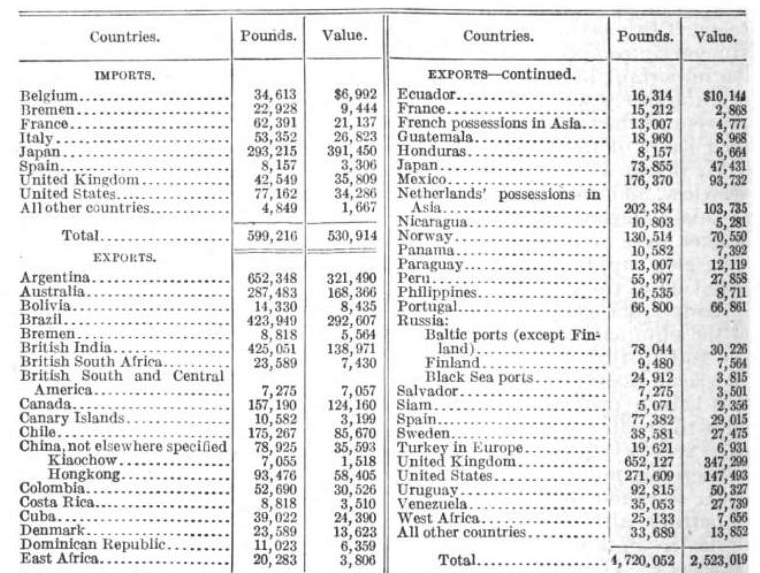

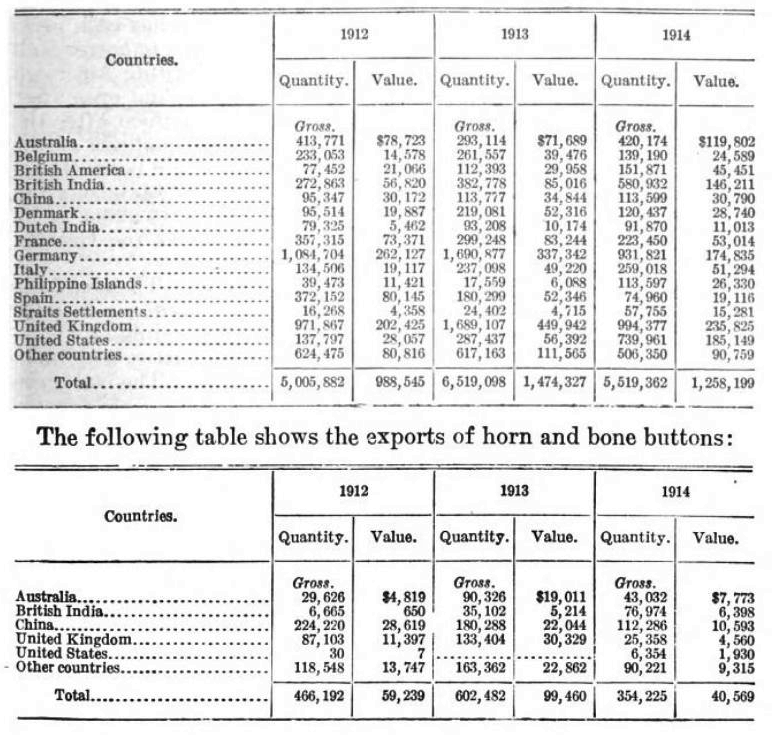

The overseas trade in buttons for 1913 (after which statistics ere not available) is below:

The report noted that prior to the development of its own pearl button trade, the United States had been the largest importer of MOP buttons from Germany. This industry had been monopolised by Viennese manufacturers during the middle of the 19th century, then from Lower Austria, Bohemia and Moravia, then from the 1870s onwards also Saxony, Berlin and Hanover. The success of the States’ own industry would practically exclude Germany pearl buttons from its market, however, there was a continued market for buttons made with feldspar there. There had been two factories in Herzogenrath that made most of the feldspar (agate, china porcelain) buttons in the country, mostly for cheap dresses and underwear. A firm in Stolberg had been a large exporter of metal snap fasteners to the USA.

Pre war buttons had been a large item of export to the USA from Berlin, with 155 button manufacturers existing in the city and suburbs in 1915, including wood, horn, metal, pearl, celluloid, glass, ivory nut, cuff, textile, patent fasteners, moulds, button making machinery and materials.

“In Upper Silesia, where there is a large Polish element, shawls are worn rather than coats, but buttons are used upon women’s dresses for ornamentation only.” In Plauen, one small manufacturer supplied the crochet and pearl buttons favoured in that region.

As Germany was self-sufficent, the report concluded that there was little scope for American firms to export there, except perhaps for novelties or patented materials.

The German Button Industry: B.I.O.S. report 1/1/47

I was surprised that such a report existed. How important could the button industry be to the British Government? Quoting from the Library of Congress … “Following right behind Allied combat troops into occupied areas, representatives of the British Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee (BIOS), the Combined Intelligence Objectives Subcommittee (CIOS), and the U.S. Field Intelligence Agency, Technical (FIAT), visited German manufacturing plants, research laboratories, and other war-related facilities to interview managers, scientists, and engineers. After collecting relevant documents, these groups wrote technical briefs on individual subjects, production processes and new technologies. They also prepared reports on whole industries – notably the German dye industry – and on construction projects, such as German underground factories.”

This report included details on thermosetting and thermoplastic resins, casein, wood, MOP, ‘natural horn’ and metal buttons as well as the machinery and chemicals used. I think the tone of the report is one of checking up on the state of the German industry, checking if there was machinery or techniques that could benefit British industry, rather than on how German industry could be helped to rebuild. Some individuals , pointedly described as anti-Nazi, were named as potentially worth taking to England for further questioning for British Industry’s benefit.

The report paints a sad picture of the state of Germany at that time … I have left spelling and punctuation as in the report.

A Resume of the report

“As far as the manufacture of moulded buttons is concerned, it can be said that nothing of any particular importance was found during the visit to Germany.”

“The Country as a whole was found to be well up to date with Injection Moulding Machinery but behind the times with Compression Moulding … due to the fact that from 1938 onwards, no progress was made as the industry was not considered essential to the war effort.”

“… German firms are able to produce a very high class product with plant very much out of date (because) they have an abundance of well trained and highly skilled labour which, because of very low wages existing, is able to replace the use of more modern machinery. The position with the wages is that no change has been made (in 1946) since 1938.”

“… by the use of cheap labour … a potential danger existed to our export market if they should be re-opened to German competition.”

The Casein Button Trade was found … to be practically non-existent since no supplies of Casein Sheet Material were available.”

“The Horn Button Trade was likewise non-existent … one firm trying to make a few Horn Buttons merely because they had nothing else …”

“The Metal Button Industry was found to be in excellent condition … Samples of their products were brought back.”

“Wooden buttons were found being made by all and sundry. This was because of the shortage of other materials. In general their products were quite crude and were sold merely because of the great shortage of buttons.”

“As everywhere, working time is 42 hours a week, due to the low calorie value of the present ration and the exhaustion of the workers.”

“In 1942 the premises (of a MOP button factory) were taken over in order to house Russian Forced Labour which was employed in a nearby factory. The factory was found to be still in a disorderly state. .. the proprietor was making a few articles from the small stock of shells which then existed in order to sell them to buy food for himself and his family. The manufacturing process was very primitive and done entirely by hand.”

In 1945 the Russian Occupation Forces confiscated nearly all (of a particular) firm’s machinery. The proprietor, however had immediately ordered new machines … (some had been delivered, but a company supplying them) … were not now in a position to deliver anymore but that when the Russians Occupation Forces had finished dismantling their factory, they hoped to be able to resume delivery again on a smaller scale.”

“The factory (of one particular firm) was partly destroyed by fire at the end of the war. The firm employed foreign forced labour which it seemed, accounted for the fire.”

Western Germany was created in 1949 when the U.S.A., Great Britain, and France consolidated those zones, or portions, of Germany that they had occupied at the end of WW2. When East and West were reunited in 1990, West Germany’s constitution and official name (Federal Republic of Germany) were adopted by the unified whole.

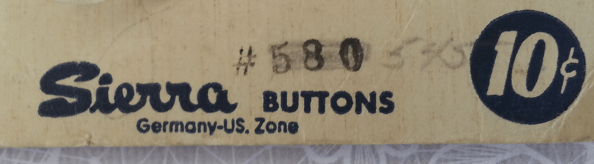

From 1887 until WW2 items for export were marked “Made in Germany” or “Germany”. From around 1945-49, goods, if marked, were marked “Made in Germany US – Military Zone”.

From 1949 until 1952-22 they reverted to “Made in Germany”, but wishing to distinguish themselves from the East, they then changed to “Made in West(ern) Germany” although this was not mandated.

Button Museums

As mentioned above, there had been a strong button manufacturing industry in Germany for centuries, particularily around Bärnau. Because of this, the German Button Museum was opened there in 1975, and displays over 2.5 million buttons made of 26 differing materials. There is also a glass button museum in Weidenberg.

Manufacturers

Wilhelm Pohl & Söhne oHG

This company in Buchenweg appears to have closed.

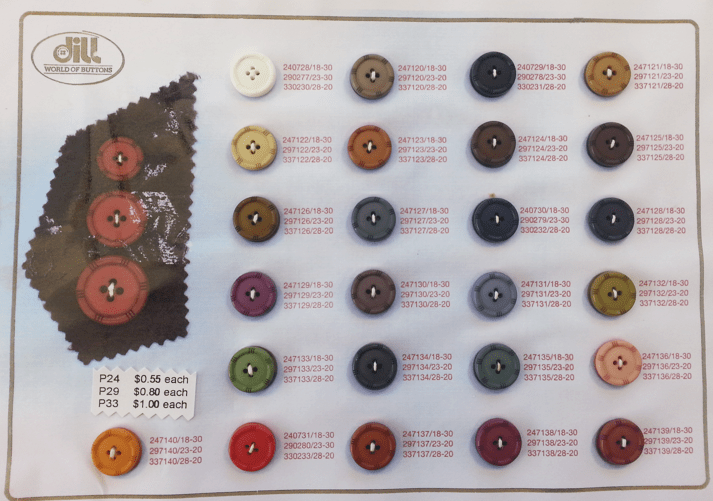

Dill

This company dates from 1924 in Barnau, Bavaria. It manufactures leather, wooden, MOP, plastic and metal buttons.

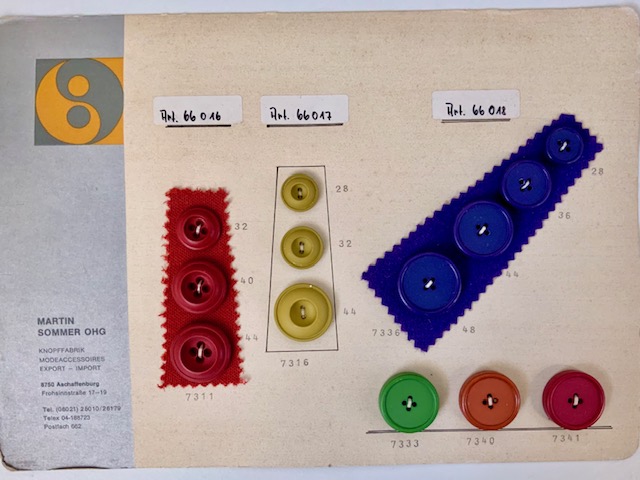

Martin Sommer OHG, Ascaffenburg

GREECE

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

In Athens there was a factory producing horn buttons, and in Piraeus one making iron buttons. Only a small quantity of cloth-covered buttons were made in Salonika.

Most buttons, including glass, bone, horn, metal and pearl varieties, were imported from Germany and Austria. Due to the war, some business was starting with English firms. Cheap prices, not quality, was what mattered.

INDIA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

“Buttons are largely used in India by the middle and better classes of natives, as well as by Europeans “. These included pearl, mainly from Japan, ivory nut and china from Italy, and metal. “There is a demand for lentille China buttons, made in Italy, on account of their cheapness”. (ED: “Lentille” is French for lentil. Were the buttons shaped like, or as small as, lentils?) Some leather, and better vegetable ivory came from Britain.

Low quality pearl, as well as horn, bone and coconut shell were manufactured locally to a small extent. Italian buttons had replaced German and Austrian, with some coming from England. Brown and white buttons suitable for tropical clothes were especially in demand.

ITALY

During the Middle ages there were in Venice craft guilds of ‘anemeri’ who made button-mould for covering with cloth. These plain, basic buttons would, by the 13th century, have changed to valuable fashion accessories made in precious metals and stone. After that, goldsmiths had a monopoly on making small objects such as buttons, of gold, silver, alloys, precious stones and crystals. This monopoly faded during the second half of the 16th century, with other craftsmen such as embroiderers, tailors, glassworkers, etc becoming involved. Venetian glass workers (paternostreri, later perleri) began exporting yellow and ‘coral’ glass buttons. Brass-workers in Milan made round brass buttons. Silk thread buttons were made in Naples, Bologna and Mantua. Around the 18th century specific “button makers” evolved, with most located in the northern regions, following the successful methods developed in England and France. In the second half of the 18th to the early 19th centuries, ceramic buttons were produced in the Veneto and Naples regions. Similar frictions that had occurred in England between older style craftsmen, and more modern, industrial concerns occurred in Italy also, particularly in Turin. The Bergamo region of Italy became a centre for button manufucturing with imported French expertise important as the local manufacturers became industrialised. In Milan, button makers specialising in metal alloy buttons started to improve their production techniques to develop, by the early 19th century, high qualitiy goods.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There were 55 button factories in Italy making amber, coral, horn, ivory, pearl, tortoise shell, vegetable ivory, wood, horsehair, leather, celluloid, gutta percha and cloth buttons, and an unknown number making papier-maché, metal, porcelain and glass buttons as by-products. The industry was centred in Milan, Piacenza and Bresica, employing 5,870 people. Italy exported buttons, particularily corozo but also papier-maché, bone, pearl, porcelain, glass and silk, around the world. In 1913 over $3,000,000 worth of vegetable ivory buttons were exported.

Pre-war they imported some buttons such as pearl, porcelain and glass items from Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Japan and Turkey. Although self-sufficent for many types of buttons, there was demand for bachelor buttons, shoe (made of papier-maché), pearl, celluloid, snap fasteners, glass and agate buttons to be met.

Papier-maché was used extensively for Italian soldiers uniform buttons! A trade in novelty items, including buttons, made of glass, cheap enamel and metal had “flourished under the stimulus of patriotism and war fever” for items of patriotic designs.

Challenges to the industry had included a cholera outbreak in 1911 that resulted in new regulations making the purchase of bone more difficult with a resultant increase in price. In 1913 there had been a decline in trade due to fashion changes and financial conditions. “When war broke out in 1914 … foreign markets were almost closed, foreign credits were unavailable, and many factories closed their doors. After the crisis passed factories reopened and a demand sprang up for cheap buttons for military purposes, but many factories are still (in 1915) running on half time. In spite of the increased price of raw materials, fuel, dyes, etc., prices of finished goods are the same and the industry is in a crippled condition.” Another challenge was that most materials for button manufacture were imported, and hence becoming scarce. There was competition for the raw materials for the making of uniform buttons.

Il Giornale Italiano (Sydney) 7th February 1934 page 3.

Stefano Pacalet: A Frenchman operating in Turin. Made civilian and military buttons Gold, silver, metal. High quality products. c. 1750-90.

Tacchini & Fanti: Corozo buttons. c. 1869-1889, then merged with the ‘Società Anonima Manifattura Bottoni’. The corozo buttons were named ‘bottoni di frutto’.

Bottonificio Fenili SRL: Created pre WW1 in Mozzo, Lombardy and accquired by EU Design in 2014. https://eu-design.com/manufacturing/

Bomisa Bottoni Minuterie: Founded 1920 making buttons (including for the Italian military and for fashion houses), fasteners, needles, pins and other metal accessories. Famous for their high quality enamelled metal buttons. It is now part of the BAP Group.

Corozite: Founded in 1931 in San Paolo d’Argon, Bergamo making galaith, synthetic wood and bone and urea buttons. Now part of the BAP Group.

B.A.P Bottonificio: Started making MOP buttons in Villongo in 1941, and corozo in 1975. https://bottonificiobap.it/en/the-products

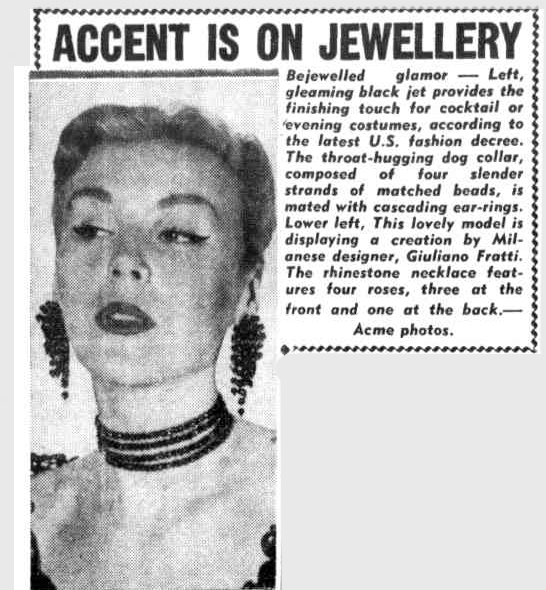

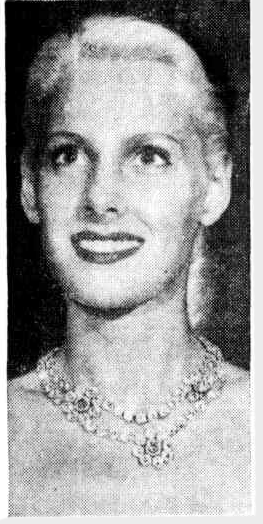

Giuliano Fratti: A MIlanese designer from the late 1930s, producing buttons, belts and buckles. He was dubbed “Mr Button”. Due to war-time shortages, by 1941 he was making buttons from alternative materials such as cork, straw, wood and corn cobs. During the second world war the company switched to the production of fashion jewellery. After the war, from the late 1940s he made French designed buttons under licence for fashion houses across Europe. He retired in 1972.

Truth (Sydney), 13th August 1950 page 48.

Bottonificio Piemontese Srl. Established in 1955, they supply Italian and French fashion designers. They make polyester, casein, MOP, rhinestone and eco-sustainable buttons in hemp, jute, corozo powder, cotton, bio-resin.

JAPAN

From 1867 Japan was opened up for trade to the West. Below are two brief references from 1879, that probably refer to cloisonne buttons.

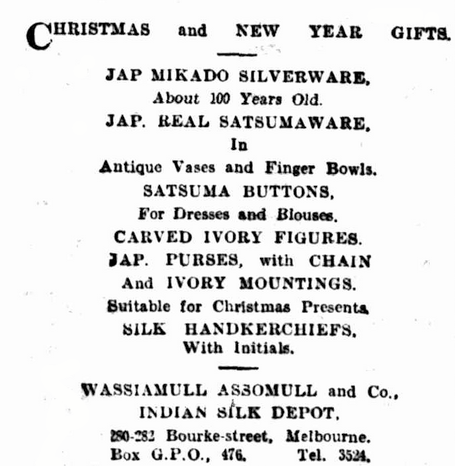

Another of the crafts modified for the new markets were Satuma ware, a type of ceramic ware made since around 1600; now made into buttons.

The Age (Melbourne), 26th December 1905 page 10.

The Forbes Advocate (NSW), 28th February 1913 page 2.

The Sunday Sun (Sydney), 6th January 1907 page 5.

Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 5th July 1907 page 9.

Southern Argus (Port Elliot, SA), 18th March 1909 page 4.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

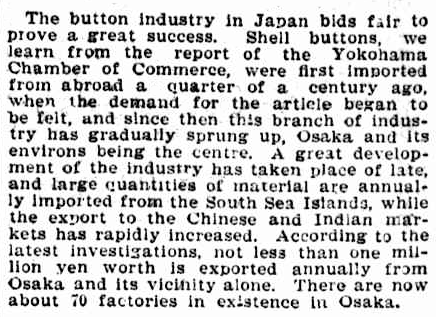

The button industry was the reverse of many countries already mentioned, in that there was limited local consumption, but a large export of shell, horn, brass and copper buttons. The metal buttons were only sold to China and other “Far Eastern” countries. In 1915 there were over 250 factories in Osaka alone.

The buttons that were imported had come mainly from Germany. These included brass, copper, rubber and covered buttons.

Recorder (Port Pirie, SA), 2nd April 1919 page 4.

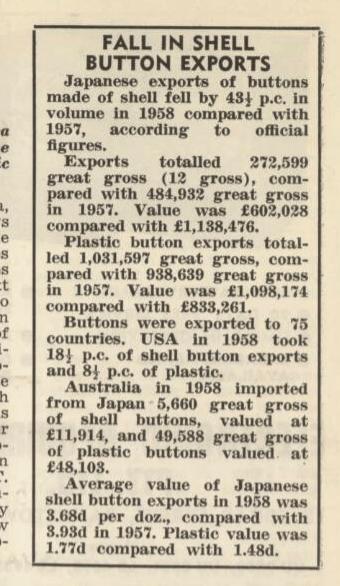

Fisheries Newsletter, June 1960 page 21.

JAVA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

No buttons were manufactured locally. Bone, pearl, metal, and glass ere imported mainly from Holland, Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan.

MEXICO

Mexico has a rich history of silver crafts. from the 1750s silver buttons/ornamnets were made for the Charro suits of the Mexican horsemen. In the 1920-50s there was a boom in production of silver and other metal buttons for the tourist and export trade.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Buttons were usually bought through French and German wholesalers. Buttons favoured were pearl, metal, horn, paste, porcelain and composition and cloth covered. There was a demand for plain polished brass and tinned buttons for military uniforms. It was noted that an officer’s dress uniform coat alone required 2 to 2.5 dozen buttons! Only poor quality pearl and bone buttons were made in Mexico.

NETHERLANDS

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There was little local industry, some bone, ivory and buffalo horn made in Amsterdam. Most buttons imported from Germany, Austria and Italy as well as some higher quality items from France and England. Popular buttons included “Steinnuss” (ED: translates stone-nut i.e. tagua nut) which “whilst very expensive, are much liked for overcoats and mantles”, also pearl, horn and linen. A demand for American press buttons existed.

The Newcastle Sun, 25th October 1954 page 5.

Although the region of Holland consisits of only 2 of the 12 provinces of the Netherlands, the name Holland came to be used to refer to the whole country.

From the International Commerce, Vol. 69, 1st April 1963.

Cards of buttons exist with the name S. J. Heigentlich and the following trademark:

NEW ZEALAND

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

No buttons were being manufactured locally. Before the war bone, and similar, came from Austria, but in 1915 they mainly came from America and England, although English manufacturers were having trouble filling orders. Pearl buttons had come from Italy, France and Japan, and now Japan was increasing its share. Metal buttons were coming from America and England. American white pearl buttons were not favoured, although some coloured varieties were.

NORWAY

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Postcard of Christiania, 1915.

Ready made clothing was manufactured in Norway, but there were only metal and covered buttons being made in Christiania so an import market existed. The traditional exporters had been Italy, Germany and England.

Common types of buttons used, in decreasing order, were vegetable ivory, bone, metal and paper/pressed cardboard. Also used were xylonite, linen, tin, celluloid, stone and glass. The lacquered pressed cardboard buttons were very cheap and came from Germany.

NOUMEA

In 1906 a company was formed for the manufacture of pearl buttons, with a factory built in the Rue de l’Alma. Equipment was imported from France for this endeavour. The factory was to employ 40 people with grand hopes for growth.

Papuan Courier (Port Moresby), 19th October 1928 page 7.

PALESTINE

The article below dates from 1942, published in the November 1948 ‘Just Buttons’ magazine. The region of Palestine was still a British Mandate in 1942. These buttons are currently referred to as ‘Bethlehem Pearls’, and have also been described as ‘Jordon Pearls’.

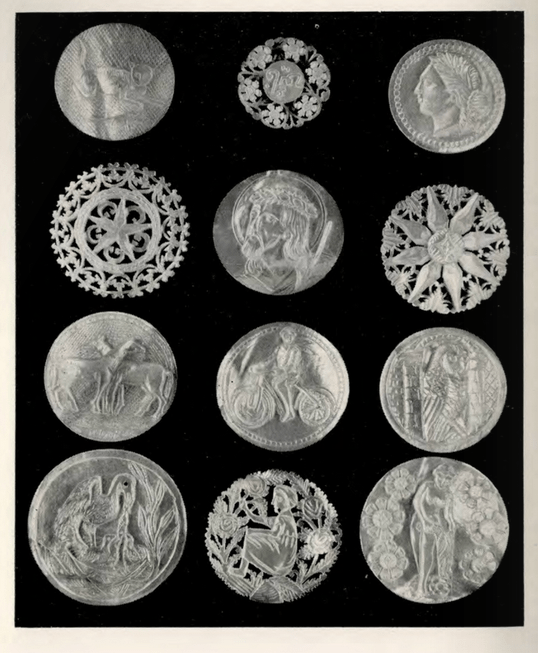

Page 34.

Page 35.

Page 52.

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

Papua New Guinea Post-Courier (Port Moresby), 5th January 1972 page 19.

PARAGUAY

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

All buttons were imported, mainly from France and Germany. Mostly cheaper buttons: MOP, bone, china, porcelain, corozo, wood, and metal bachelor’s buttons. Due to the local climate, the demand was for light coloured buttons for their light coloured clothing. Most clothing was made at home, with the few wealthy people buying their clothing overseas.

PERSIA

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Cloth covered buttons were made in small quantities. Bone buttons were preferred.

PERU

From pre-colonial times local artisans were skilled metal workers. Large quantities of silver mined in Peru in colonial times, with buttons made in the ?19-21st century.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There was no manufacturing of any buttons. Buttons of all types were imported, mainly from Germany, excepting for vegetable ivory from Italy. Japan had just introduced imitation pearl buttons with increasing sales. Favoured types were vegetable ivory, MOP, metal, horn, glass, bone, glass, composition, porcelain and ivory. Small black glass buttons were important for mourning clothes. Popular types included small novelty, small coloured glass and small brass buttons, also fancy vest buttons and shoe buttons.

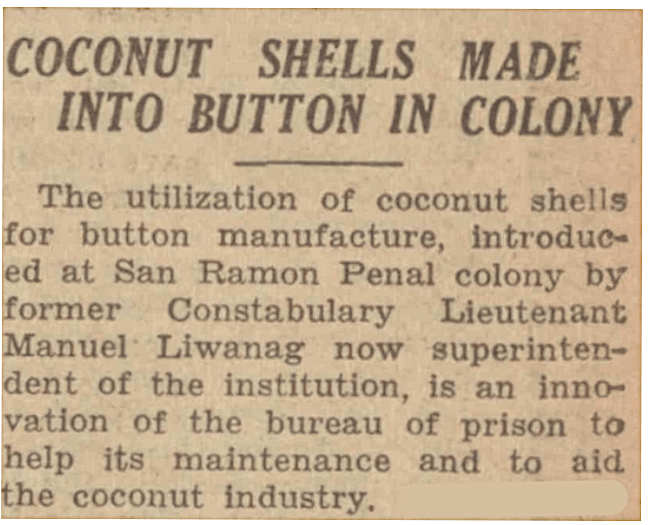

PHILIPPINES

In 1902 it was reported that Filipino tailors made use of locally made buttons as well as imported stock. The locally made items included simple polished wooden disks or domes, the wood including caphor, ebony, and sandalwood. There were also buttons made from locally sourced metal nuggets, and from water buffalo horn.

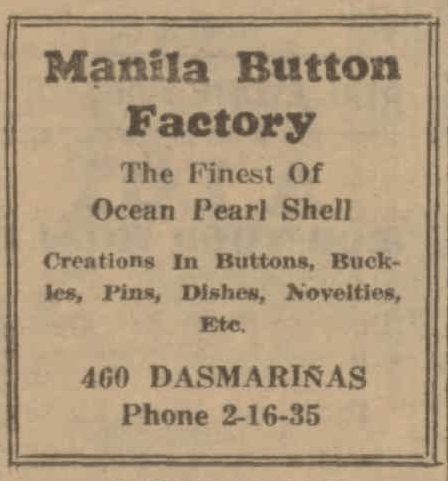

A ‘Manila Button Factory’ existed for at least 1932-1945.

The Tribune (Philippines), 8th May 1934 page 10.

The Tribune (Philippines), 23rd June 1937 page 1.

Tribune (Philippines), 4th June 1939 page 27.

Tribune (Philippines), 24th April 1943 page 2.

PORTUGAL

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Inferior quality buttons were made at around 8 factories in Oporto from horn, corozo, pearl, glass, slate, wood, metal and cloth. Higher quality products made from glass, porcelain, coloured aluminium and other materials had been imported, pre-war, from France, Germany and Austria. As supplies from these countries had ceased, stocks were low in 1915.

The only exportation of buttons was a small amount to Portugese colonies.

Louropel

Founded in Portugal in 1966. Producing buttons, toggle and buckles from from polymer, urea, nylon, metal, horn, coconut, cork, bone, corozo, wood, and recycled polyester.

RUSSIA (INCLUDING FINLAND)

Faberge made buttons around the turn of the 20th century, in pearl, gold, diamond and enamel.

These are in the Cleveland Museum. Image sourced from Wikimedia.org

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There existed 28 button factories in Moscow and Lodz supplying cheap coconut, Steinnuss (vegetable ivory) and horn buttons. These had existed for less than a decade (in 1916).

The most popular type of buttons in the Caucasus were the cheap four-hole types made from coconut in Moscow. Also popular were imitation-ivory made from composition. Most imported buttons came from Austria-Hungry, and most of these were pearl. Linen and steel trouser buttons had been imported from Poland, but at the time of the report this supply had been completely cut off.

In the Riga district, most buttons had come from Germany and Austria, including buffalo horn, linen, horn, jet, glass, pearl and steinnuss. There was no local manufacturing in this district, and button stocks were very depleted, with dealers hoping to gain supplies from the USA, despite the city’s population being only half of normal, and money tight.

Finland: Note that Finland was part of Russia until declaring independence in 1917.

There was insignificant manufacture of buttons, with 2 or 3 factories doing a small amount of business. Most buttons used locally were bone or horn, but not shell, from Germany and Russia, and Denmark, with better class buttons from France.

SPAIN

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Spain had a significant button industry but still imported a third of its requirements. Its export market had increased due to war time shortages. There were 85 factories making stamped metal items, including buttons, in Barcelona; 18 making imitation pearl in Cardeau; 1 making only vegetable ivory in Gerona and 5 making a variety of non-metal types including bone. Pearl buttons were made in Valencia. Many of the factories were no more than small workshops. Buttons were also made in considerable numbers in homes. Two factories in the Madrid district made cheap grade white metal and brass uniform buttons.

Buttons used locally included bone, imitation pearl, real pearl and novelty buttons, also metal and Irish crochet, horn, celluloid, china, porcelain, composition, papier-maché for shoes and gaiters, and metal and gutta-percha for trousers. Pre-war buttons imported buttons came from Germany, France, Japan and Austria. Composition buttons were called ‘botones de pasta’ and ‘botones de coco’.

There was only one factory making snap fasteners in all of Spain which was unable to meet demand. Most imported snaps had come from Austria; with the closure of this market prices had risen from 40-80cents to $2.50 per gross. Novelty buttons were also in low supply. Black glass were in demand for mourning buttons.

STRAITS SETTLEMENTS

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

These territories now form parts of Malaysia and Singapore. There was no local manufacture. Fancy buttons were imported from Germany, Austria and England. The war had resulted in shortages.

SWEDEN

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

There were only 4 button factories in Sweden. These made uniform buttons of brass, nickle, iron and lead, including “yellow anchor buttons” for boys clothing. Some were exported to Denmark. Ivory nut and pearl buttons for underwear and shirts were the main demand, also bone, glass and covered; Germany and Austria had supplied most of the pearl buttons and Italy the ivory nut, and England textile covered buttons. German buttons were said to be half the price of American.

AB Sporrong

Sporrong manufactures uniform button, badges and emblems, and other products. It began in Stockholm in 1666 and was taken over by Mr Sporrong in 1842. Since 2018 it has been owned by Kultakeskus OY, a metal processing company. products are produced in a factory in Estonia and elsewhere.

SWITZERLAND

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Metal buttons, primarily used for uniforms, were the only type made in Switzerland. Vegetable ivory (steinnuss) for men’s clothing predominated, also cheaper metal trouser buttons. Fancy buttons of celluloid, glass, cloth, horn, wood and galalith were sold. It was noted that although it had been discovered 10-15 years ago, galalith had only been successfully used for buttons for 4-5 years. Supplies of casein to make it were unobtainable; however, there were large stocks of galalith existing. The Swiss were having no issues obtaining supplies of buttons from the “belligerent countries”. Therefore there did not seem to be encouragement for American manufacturers to sell here.

A report into the production of the film “War and Peace” in 1956 stated that “an entire button factory in Switzerland is working full time just to produce the 100,000 buttons needed for the film’s costumes.”

This Swiss button and accessory manufacturer existed from 1952 but is now in liquidation.

TURKEY (INCLUDING BERUIT AND SMYRNA)

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

“In the Anatolian peasant costume, buttons are entirely eliminated in the trousers, which close by means of a cord, like a bag, around the hips. The short, vest-like coat is provided, like all underwear, with cheap porcelain button, which are imported from a few firms in France, Germany, Austria, and Italy.” In 1909 the manufacturers had formed a syndicate and bumped up their prices by 40%. A colour called ‘mineral’, a tone between gray and brown, was the best seller.

Traditional costume of a village bride from the central district of the Sivas province, Central Anatolia. Photo from Pinterest.com, by Jean-Marie Criel.

Traditional parade costume of the people’s militia from Dinar, Central Anatolia. Photo from Pinterest.com, by Jean-Marie Criel.

All buttons were imported into the District around Beirut. About 80% of these were bone buttons from Italy. The other 20% were from Germany and France.

All buttons were imported into Smyrna including pearl, glass, stone, pasteboard, cloth and wood, from Italy, Austria, Germany and France. Metal uniforms, mostly galvanised, were used for the military.

UNITED KINGDOM

General History

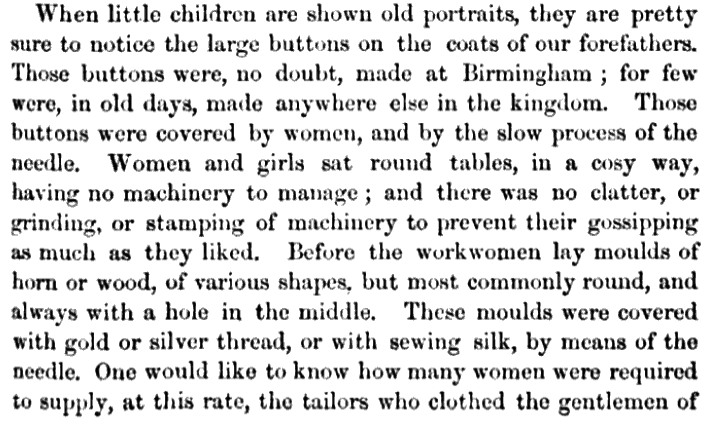

“The first manufactory of (buttons) on a large scale was established in the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603), and the trade rapidly grew into importance. In 1661 the manufacturers had sufficient influence to procure an Act of Parliament forbidding the sale or importation of foreign buttons whatever under a penalty of £50 on the seller, and £100 on the importer … 30 years later the Act was renewed by William III … Some ingenious persons commenced making buttons of wood only, but William III again stepped in, and another statute was passed enacting that no person should make or sell a set of any buttons made of wood only. One too clever man tried to evade the Act by pleading that his buttons were not made of wood only, by reason of their having a wire shank, but his plea was of no use … William imposed a penalty of 40s 8d per dozen on all persons making or selling buttons covered with cloth or any material except velvet, of which clothes were usually made, the object being to encourage the manufacture of the gold and silver buttons. Queen Anne (1702-1714) increased the penalty to £5. George I (1714-1727) tried his hand in enforcing similar protection, and not only extended it to button holes, but went so far as to make the wearer of the offending garment liable as well as the tailor. This was probably in consequence of a petition presented to Parliament that needle-wrought buttons* had been a manufacture of considerable importance. However tailors continued to make cloth buttons and button holes. Birmingham seems to have had a monopoly on the trade, as there is no company of button makers in London.” Edited from a longer article in The Sydney Morning Herald, 15th December 1891; originally from the London Globe.

*In the 17th to 19th century large volumes of needlework, lace and Dorset type buttons were made as a cottage industry in Dorset, Buckinghamshire, Leek and Maccelsfield. This declined due to competition by the metal button industry of Birmingham.

In the eighteenth century, enamelled buttons were being made both in Bilston and Battersea.

Health, Husbandry, and Handicraft: by Harriet Martieau in 1861 , pages 539-40.

Glen Innes Examiner and General Advertiser (NSW), 17th June 1898 page 2.

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

Men’s suits (coat, vest, trousers) were usually trimmed with vegetable-ivory. Overcoats required large horn buttons. Tweed suits and jackets sometimes used leather or galalith. Morning coats, which were not being worn as often, used silk covered buttons. Khaki uniforms required metal buttons made in Birmingham. Women’s suits had either vegetable ivory or cloth covered. Cloaks used fancy celluloid or celluloid and enamel. Underwear, shirts and blouses used pearl. Some underwear used linen buttons. Printed celluloid were also popular for women’s wear.

Pearl buttons had been imported from Vienna, but were now coming from America, Japan and France. Buttons were previously imported from Austria-Hungry, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and elsewhere. Because of the war, Austria and Germany were not trading, and France and Italy were not able to supply as much as usual. In general, prices had risen considerably since the start of the war.

There was less ready-made men’s clothing made in England compared with In the USA, so British tailors did a relatively larger trade in buttons than American. Some button types, for example galalith buttons, could no longer be obtained. Metal buckles, snaps and clasps were in short supply.

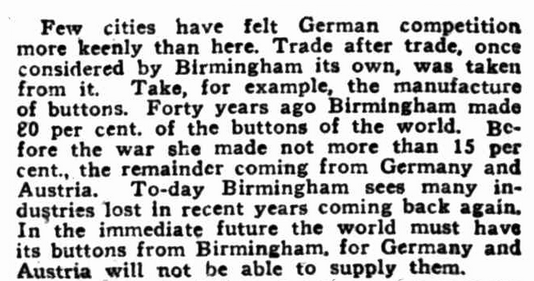

In 1916 Birmingham, the largest button manufacturing centre in the UK, had around 20 firms pouring out an estimated 9,000,000 gross annual output due to the large military requirements. Also, British firms were meeting the local short fall of $10,000,000 to $15,000,000 of pre-war imports from Germany and Austria.

Since 1865 pearl shell had been obtained from Australia, but in latter years this had become more expensive, so that celluloid, galalith and “variable vegetable preparations” were tending to replace shell.

In Bristol, the production of woolen clothing by both outworkers and factories, including for government contracts, used a lot of buttons. Buttons were also needed for the export clothing trade, and for the manufacturing of waterproofs. The clothing factories of Leeds, “second only to London in size” used large numbers of vegetable ivory buttons, also bone, horn, celluloid and tin, none of which were made locally.

Nottingham had an extensive industry manufacturing blouses, hosiery, gloves, and footwear that needed buttons, including fancy coloured glass, vegetable ivory, pearl and xylonite for women’s wear; metal, bone, vegetable ivory and cloth covered for menswear; papier-machie and pearl for footwear. Pre war only 5% of these buttons came from Britain. Some covered, bone and vegetable ivory had been made locally. Demand for American stocks had increased.

In Wales, no buttons were made. No buttons were imported directly. All were imported from or through places such as Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and London. There was a need for strong workwear buttons from the industrial centres.

Buttons were not manufactured to any extent in Scotland but imported from Austrian, German and English manufacturers. It was felt that American buttons were too expensive to compete with other markets for menswear, but that this was not a problem for women’s fashions where originality and variety were more important than price. In general the quality of buttons and cloth were not as good as they had been. Before the war “black braid buttons made in Barmen, Germany” were popular in Glasgow, as were ivory nut. Fresh water pearl buttons “plain, white, smoked, fancy, coloured and carved”, were being imported from America, as were ivory nut and papier maché. Japan and Italy were also supplying buttons. It was noted that the quality control of American pearl buttons was not as good as that of the Japanese.

The only buttons made in Ireland were crochet buttons. The local clothing industry was centred in Belfast, using large quantities of pearl and bone (actually vegetable ivory) buttons, with composition coat and metal trouser buttons from America. The better quality pearl buttons were bought from England, lesser quality from America, England and Italy. It was felt that the British and American metal and composition fashion buttons were inferior to the Austrian and German ones they replaced.

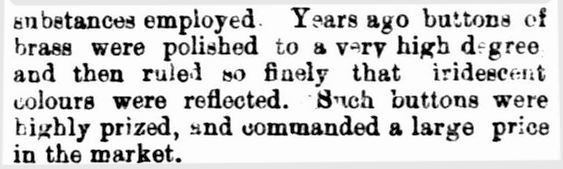

Irish crochet buttons from a 1908 pattern book.

Ireland

In the 18th-early 19th century there was a strong trade of die-sinking in Dublin, with many making buttons as well as medals and seals. Dr. William Fraser wrote in 1885-6 in the ‘Journal of the Royal Historical and Archealogical Association of Ireland’ that ” Actual button making has been extinct for many years … (In 1765 and for many years afterwards ) … “the trade of die-sinking in Dublin was renumerative; for there was much demand for buttons struck in metal, which was so well paid that the workmen who fabricated heavy gilt buttons then in ordinary use for gentlemen and their servants’ liveries – were able to earn large wages, and seldom worked above three, or four days each week … Change of fashion has long destroyed this lucrative employment … from about 1750-1800, buttons were made quite flat, of a single plate of metal with the stem brazed on the back. The domed button (convex) was still a single plate, came into use about 1780 (until about) 1820. After that the button made of two plates joined together around the edge came into general use, except in the case of servants’ livery buttons, many of which are still made into flat or convex single plate form”

Bogwood buttons (often from oak or pine long submerged in peat bogs) were made in Ireland, mostly in the 19th century.

Malta

Information from the ‘Department of Commerce of USA, Special Consular Reports, Foreign Trade in Buttons: 1st April 1916’

At the time Malta was a British colony.

Most button trade was done by tailors, as there was no ready-made industry. Pre-war they were imported from Austria-Hungary, Germany, France, Italy and England. As most Maltese were of the agricultural class, cheaper buttons predominated.

Port Lincoln Times (SA), 4th December 1936 page 7.

Geraldton Guardian and Express (WA), 18th March 1941 page 4.

The Evening News (Rockhampton,Qld), 29th March 1941 page 5.

Wodonga and Towong Sentinel, 19th December 1941 page 4.

Bunyip (Gawler, SA), 24th July 1942 page 1.

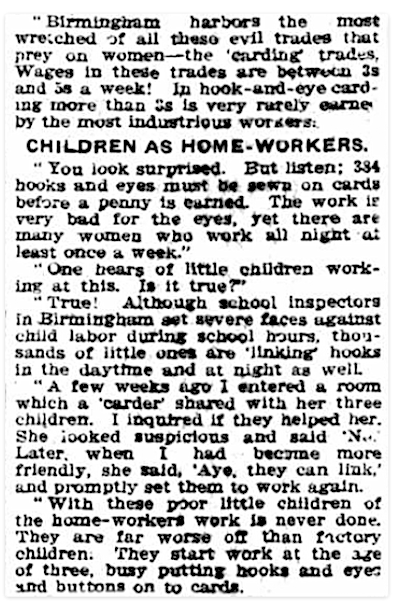

Birmingham

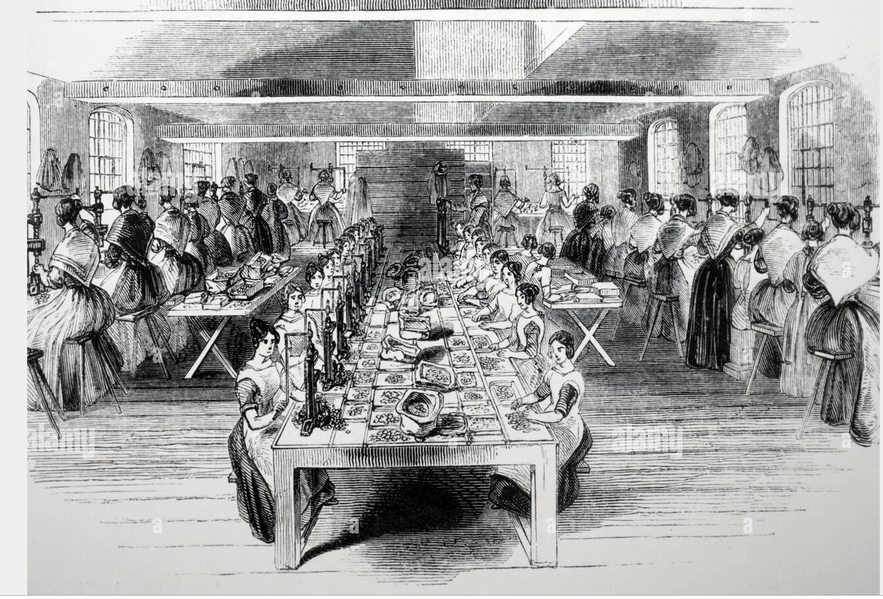

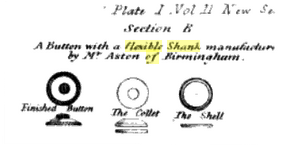

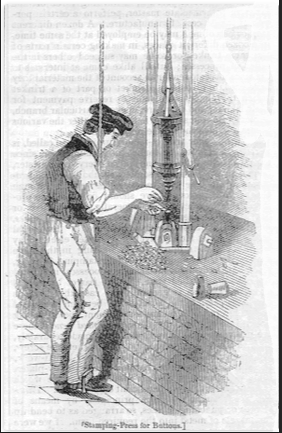

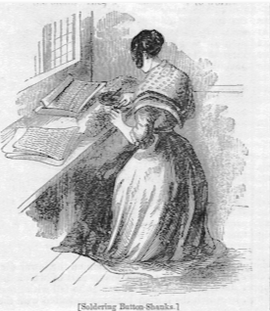

Illustration showing workers making gilt buttons, Elliotts factory, Birmingham: die-stamping button blanks. 1844.

Birmingham was one of the main button making cities of the world.

Early history

Birmingham’s growth from a 7th century village to a 12th century market town to a large city in the 19th century was largely based on metalworking industries. Textiles, leather working and iron working were local industries from medieval times. The button production started in Birmingham in the Middle Ages using horn and bone from the local meat trade.

By the early 16th century, the metal working industry was increasing in importance, with tools, knives, nails and other goods being made by an increasing number of smiths and artificers then traded to cities around Britain, and later, the world. The trade became specialised, including hiltmakers, bucklemakers, scalemakers, pewterers, wiredrawers, locksmith, swordmakers, solder and lead workers. An act prohibiting foreign button importation in 1662 encouraged the local production of buttons. The earliest records of local button makers start in the 17th century.

18th Century