Fundraising buttons (badges/pin back buttons)

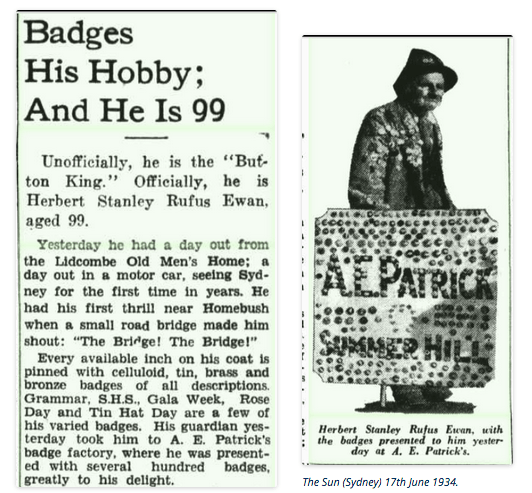

The idea for the first “Button Day” for patriotic fundraising was suggested around in April 1915, possibly by a Mr H. C. Tucker of Colac to raise funds for the Belgiums. Right from the start fundraising buttons were intended for collecting, and people did! Stories appeared in newspapers about these collectors. Sometimes mothers passed on their war time collection to their children. Members of the Patrick family (manufacturers of many of the buttons) built up impressive collections.

There were buttons for ‘Wattle Day’, ‘Flag Day’, ‘Red Cross Day’, etc, etc.

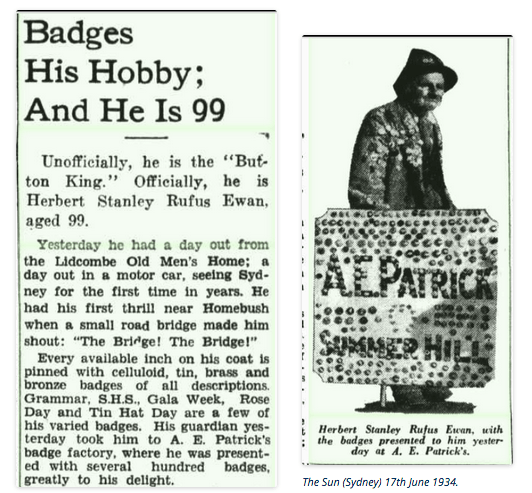

The Sun (Sydney) 17th June 1934 page 7.

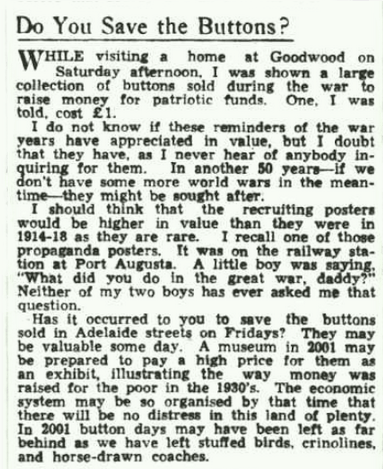

News (Adelaide) 23rd June 1936 page 4.

From an article in The Weekly Times on 16th march 1929:

“Button days are fairly numerous – hundreds have been held in Australia since the “war series” began, and collections of the buttons sold for war funds and charities have no lack of variety in their field. Buttons of this class, of course, are much less interesting, generally, than military buttons, though many of them are attractive to the eye. Those of the war period are becoming

scarce, at least some of them are, but may have no special value.” The writer may have been surprised at the value of fund-raising buttons now!

The Patrick family:

Considering that millions of fundraising buttons were made and sold both during and after WW1, it is amazing that only one family was responsible for most of their manufacture.

Mr Arthur William Patrick of Melbourne was printing, coping, enlarging, colouring and enameling photographs from around 1887. He was the first to make celluloid buttons in Australia. A brother, Mr Alfred Ernest Patrick, set up a photo medallion and picture framing business in Redfern, Sydney around 1899. A third brother, Mr Walter Francis Patrick, started producing buttons in Adelaide in 1918. In that year Mr A.E. Patrick estimated his factory alone had made buttons of over a thousand differing designs in a 2 year period. About 2 million buttons a year were being made for the ‘Commonwealth Button Fund’ which oversaw fund raising in Melbourne. During WW2 more than 7 million buttons were produced from Sydney.

Mr A.E. Patrick

The manufacture of these buttons involved multiple steps. The design was printed on paper then adhered to celluloid sheeting. The buttons were then cut by die from the sheets. The tin shells to which the designs were attached were cut from thin sheets of tin by a power press. Thicker tin was also cut by press for the backing of the buttons, including cutting the clip for the pin. The pins were attached by hand before all the parts (print, shell and back) were feed into a machine for clamping together. It 1918 girls were being employed to point the pins by hand, but a machine was being developed to automate this process!

Working with celluloid could be dangerous. There were fires in both the Melbourne and Sydney factories. Post war the Patricks were still making buttons for fundraising as well as for cricket and football clubs. The company continues today as ‘Patrick Australia’. See https://www.patrickaustralia.com.au/about/

Museum Victoria: 1917

Some competitors included Edmond Platt-Ruskin and Alfred Edward Seymour Stokes, both of Sydney, Thomas George Keiller, of Windsor, Melbourne, and Atkinson & Co. of Adelaide.

Museum Victoria: “On Active Service” fund 1917 by Alfred E S Stokes.

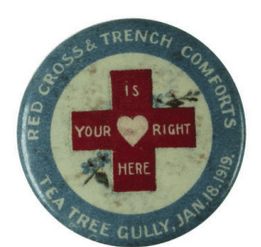

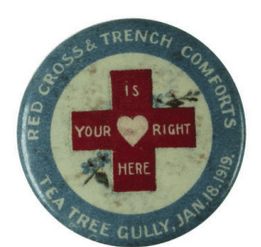

Museum Victoria: Red Cross and Trench Comforts, 1919 by Atkinson & Co.

A large number of buttons were produced in South Australia. An article about this was printed on 16th September 1933 in the Adelaide newspaper, The Mail:

Since the early war days until today, much South Australian history has been written on small

celluloid buttons, pasted on tin and sold in the streets for sixpence or 1/- each. Every new phil-

anthropic movement and every annual appeal with a sufficiently large backing has added to the store of buttons, which has grown incredibly in the past 18 years. Today they are mostly simple,

cheap strips of celluloid, making a plea for unemployment relief, baby welfare, the prevention of cruelty to animals, help for the blind, the sick and the needy. Black lettering on a white background is sufficient for most peace-time appeals, and the lettering simply states the name of the society which is canvassing your sixpence. But during the war buttons were rich and colorful. They pleaded, commanded, and sometimes almost threatened. They were covered with landscape paintings, with old heroes, or contemporary Victoria Cross winners, with guns, flags, and British bulldogs. Every one carried an appeal to the people’s emotions. Even now it is difficult to look at a collection of old buttons without feeling something of the stress and

urgency of war days. Their colouring was sometimes crude, and their sentiments occasionally got a bit out of hand. Modern anti-war propaganda has taught people a lot about the folly of hating one’s fellow man — even on celluloid buttons.

But foolish or not in their appeal, those buttons raised enormous sums for what were then the most vital needs of the day. As many as 100,000 would be struck for a Red Cross button day in South Australia alone, and on one occasion an order for 300,000 came to Adelaide from Victoria. An Adelaide printer who handled the bulk of the orders said today that in 1918 his firm must have issued millions of patriotic buttons. One of the most complete records of war-time souvenirs is hung in the Hindmarsh Council room. It contains 1,100 buttons, every one of them different, mounted on a heavy blackwood frame. The donor was Mr J. F. S. Monten, of Fitzroy, and the collection was made by his late uncle. It is almost impossible to pick out the earliest issues, for no one in 1914 or 1915 thought it worth while to date the buttons; the war would be over in a few months (it was thought). One early button was small, plain, and violet-colored, ‘Remember the Dardanelles’ was printed on it. Lord Kitchener, looking grim against a Union Jack background was pictured on another early one. So was Gen. Foch, above whose smiling face was written the immortal challenge ‘Ils ne passeront pas’ (they shall not pass). Lloyd George was a hero in those days. Several issues showed the little Welshman, dark-haired then, silhouetted against the Union Jack, with ‘Britain’s Prime Minister’ for his title. There was another of Jellicoe, circled by a laurel wreath. Much later in the day came Pershing, generalissimo of the American forces. The button designers soon struck an Australian note. An Australia Day badge for 1916 showed a kookaburra calling ‘Coo-ee’. In the same year Red Cross funds were augmented by a picture of a nurse tending a wounded soldier. ‘For kith and kin’ this was called. Brig.-Gen. S. Price Wei was the subject of a popular button and so was Gen. Blrdwood. The Wattle Day League issued a sober brown and white button, for ‘Our Stretcher Bearers.’ The War Horse Fund came out with a rather touching head of an old brown horse.

Australia Day, 1918, the most prolific of all button days, was contributed to even by the Engineermen, Fireman, and Cleaners’ Association, which struck a special button showing a train. A kookaburra with a German helmet in its mouth threw out this challenge, ‘Come Over Here.’ and a young Anzac was represented saying ”Cheer Up. We’re Boxing On.’ Even the boxing kangaroo was made into a button, appropriately entitled ‘The Fighting Kangaroo’ — Let ‘Em All Come.’ The Old Gum Tree at Glenelg in I915 was made the subject of a patriotic button, inscribed ‘Our Brave boys.’ Sir Sidney Kidman figured on a Kapundna button. A little piccaninny, as black as boot polish, with a scarlet handkerchief around her, was pictured on a Soldiers’ Fund badge. The merchant service received its tribute in several buttons. This service did splendid work at many backdoor jobs, and the public was eager to show its gratitude to the men who engaged in mine sweeping, and other works carrying very little glory and very much danger. One merchant service button showed a full-rigged ship, and it was inscribed ‘By Peril We Live.’ This was in April, 1917, and the proceeds went to the Missions to Seamen. The French Red Cross came early into the picture, and was aided by many brilliantly colored buttons, most of which depicted young France riding triumphantly over Germany.

Only towards the end of the war did this high spirit falter, and then there was a 1918 button which showed a mother and her two ragged children leaning against the ruins of what had been their home. A somewhat similar change was noticed in the trend of Australian buttons. A British bulldog standing on the Union Jack, inscribed ‘Come On’ set the pace for the early ones. As late as December, 1917, the Wattle Day League issued a medallion of an old, battered bulldog, with his left forepaw bandaged, under which was written ‘Bruised. But Not Beaten.’ And six months later the bulldog was replaced by a blue bird, asking help for the soldiers’ widows and orphans. Some of the glory had gone out of war by that time.

The farming districts were putting sheaves of wheat on their patriotic buttons at that stage. Kersbrook had a bunch of red apples, and Kingston was represented by a large red lobster. Roses, grapes, and other peaceable symbols dominated the whole of that colossal 1918 issue of buttons. Some symbols were poignant. There was a small, blue button against which the pale face and white hair of Nurse Edith Cavell was silhouetted. There was also a picture of a liner,

with the word ‘Lusitania’ beneath it. Old Nelson in his cocked hat, surrounded by a gold frame, was the subject of a 5/- colored war-time button. ‘Nelson With Us Still’ was the legend; and Lloyd George, his hair now white, was in the centre of a large medallion, emblazoned ‘Victory’

on top and ‘Peace’ below. Violet Day brought forth some pretty buttons, but the mauve and

purple tones in which they were painted have now faded to grey. There are still traces of color in one which has a white cross and a wreath of violets above a crown. Color ran riot in a button struck to obtain funds for the relief of Servia, (as it was then) Syria, and Armenia. The sky is a bright blue, the sand is gold, and above the palms in the picture rise slim, white minarets. Another strongly colored button was issued for the Red Cross Appeal in 1918. A nurse and a young soldier laughed out of it, side by side. French symbols continued to be very popular. In 1917 the tricolor was flaring over many buttons, and patriotic South Australians were carrying ‘Vive La France’ pinned to their lapels. “I won’t buy Enemy Goods” declared Britannia on another button. A grey war tank crawled across a 1918 badge, and Beatty, then merely ‘Sir David’, with his cap at a characteristic angle, looked out of dozens of buttons. Old Papa Joffre, very white-whiskered, had several buttons to himself when the French alliance was at its strongest.

Many badges commemorated the records of South Australian battalions. ‘The Glorious Eleventh’ showed a badge of chocolate and blue. ‘Well Done 44th’ was on white and blue. On a different arrangement of the same colors was ‘Good Boys. 48th. ” In a large ‘C’ the Gawler Trench Comforts Fund appealed for ‘Coffee, Cookers, Clothing, and Cinemas.’ The Soldiers’ Home League took ‘Faith’ for its inspiration, and inscribed its button with ‘Faith in the justness of Our Cause.’ Every now and again the line ‘Lest We Forget’ appeared, usually against a sombre background, or showing an angel trailing clouds of glory. One of the biggest buttons issued

during that time came from the Burra Cheer Up Day committee, which had ‘God Bless Our Men’ inscribed on a badge of wattle and flags. ‘Brick Days’ were valuable means of raising money for patriotic causes. Each brick represented a certain contribution to a fund, usually the Soldiers Home Fund. ‘For Them’ was the title of a button struck in 1918. It showed a soldier looking at his wife and baby, and the artist, whoever he or she was, made a moving study of the little group. One of the most artistic of the time was Mount Barker’s Australia Day button, which depicted a high white lighthouse at the edge of a green covered cliff. Black and gold was the badge for Peace Loan subscribers in 1919, and white searchlights played effectively over the Navy Day badge of 1918. A single cannon commemorated Verdun on a 1917 button, and a cheerful hockey girl was the symbol employed for the S.A. Women’s Hockey Association drive in aid of the Prisoners of War. The Army Nurses chose Florence Nightingale for their badge.

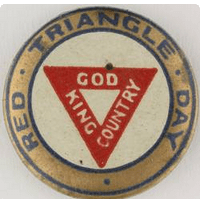

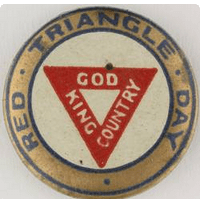

As the war went on, appeals for injured soldiers became more frequent. The Wattle Day League in particular appealed for ‘Maimed Soldiers,’ The Y.M.C.A. had many button days, and the red triangle became a familiar symbol. ‘With Our Boys Always and Everywhere’ was the Y.M.C.A.’s button day slogan. As the war years went on nearly every country town of any size was striking buttons for local patriotic endeavors. Even Oodnadatta, far up on the North-South line brought out a button, which showed an Australian soldier seated on a camel. Victor Harbor had a singularly lovely picture of masses of white spray leaping up against blue sea and sky. After the armistice and the slackening of repatriation efforts, buttons became fewer and fewer. Button

days which had been an almost daily occurrence came round weekly, then monthly. One of the last of the wartime buttons was struck for Anzac Day 1920. It was a vital, arresting study of a young digger sounding a bugle. ‘They Answered’ was written below.”

For all comments and questions, please use the Contact page.